Published: 30 July 2016

Last updated: 4 August 2016

Sulaiman “Souli” Khatib was only 13 when he first joined the Palestinian organisation Fatah. The next year, he and a friend stabbed Israeli soldiers, and were sentenced to 15 and 18 years in prison respectively.

Over the next ten years, while incarcerated in Israeli prisons, Khatib read ceaselessly about historical figures who had achieved freedom from oppression for their people. “I studied the movements of Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr. and the American civil rights movement, and of course Nelson Mandela,” he told The Jewish Independent. “We used to call prison ‘the revolutionary university.’”

When he was transferred to a prison in Nablus that had a sizeable library, Khatib began to read about Jewish history and the Holocaust, for the first time in his life. “It affected me deeply, and enabled me to see things differently,” he said.

In 1997, at age 24, Khatib was released from jail, having spent over a decade behind bars. Not long after, a new era of bloodshed engulfed Israelis and Palestinians when the Oslo Accords of 2000 didn’t seem to be delivering the freedom for Palestinians they were thought to have promised.

As the intifada intensified, Khatib began to advocate in the Palestinian community for the benefits of non-violent struggle, which he’d learned about in jail. But his efforts fell on deaf ears. “There were lots of bombings and killings of civilians during that time, and this was against my moral beliefs,” he said. “I became a stranger because of the atmosphere that existed.”

Khatib said he was forced to distance himself from the mainstream of Palestinian activists, who supported the use of violence to win their freedom from Israeli control. “So I looked for alliances in the Israeli community, for those who are also looking for different voices,” he explained.

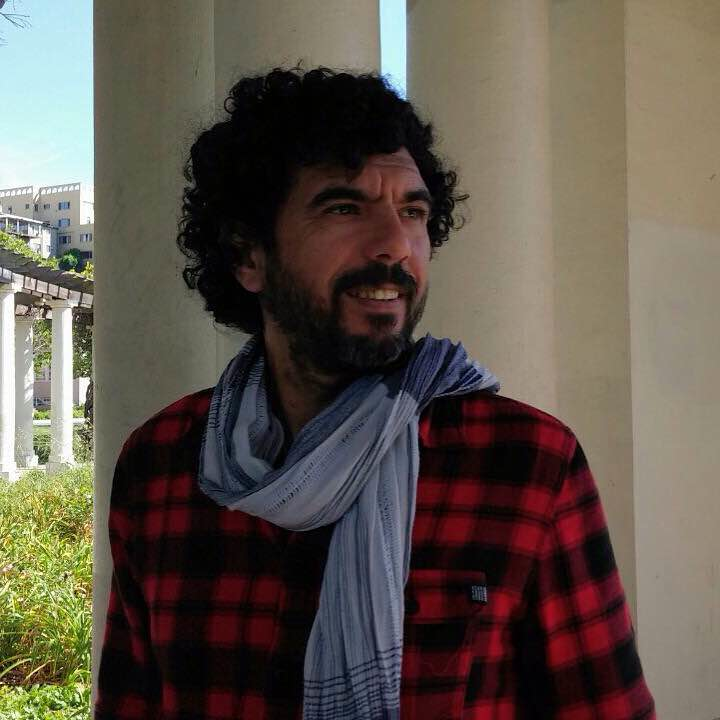

Sulaiman (Souli) Khatib

Sulaiman (Souli) Khatib

In 2005, as the Second Intifada was drawing to a close, Khatib and a few Palestinian friends - who’d also taken up arms against Israel before embracing non-violence - met with a small group of former Israeli soldiers who wanted to understand the other side. An Arabic-speaking Israeli activist made the introductions, and the two groups - about five people from each side - held secret meetings in Bethlehem where they shared their stories with their one-time enemies.

The meetings took place in secret for a year before going public in the spring of 2006. On a day in April of that year that fell during the Jewish festival of Passover and was also Palestinian Prisoners Day, Khatib and his Palestinian and Israeli ex-combatant colleagues held a public event in the Palestinian village of Anata. They announced the creation of a new organisation, Combatants for Peace. The turnout was encouraging: between 400-500 people, both Israeli and Palestinian, attended the event.

Khatib, 44, now lives in Ramallah. And Combatants for Peace, which celebrated its 10 year anniversary last month, has grown into a movement with hundreds of members, both Israeli and Palestinian, most former fighters who have since put down their guns. The group is devoted to ending all violence in Israel and the Palestinian territories and achieving peace, justice and human rights for everyone living there. Because Combatants for Peace views the occupation as a form of violence, ending it is a primary goal.

To promote its objectives, Combatants for Peace holds joint lectures - sometimes public, sometimes private - where a former Israeli soldier and a former Palestinian fighter each talk about their experiences with violence. The group also organises demonstrations, conducts educational lectures and field tours of the West Bank for the Israeli public, and educates Palestinian youth about the virtues of non-violent struggle.

Combatants for Peace is organised into about a half dozen “activity groups”, linking Israeli and Palestinian cities or towns located relatively near each other. Thus there’s a “Jerusalem-Ramallah” activity group, and another for Tel Aviv and Qalqilya. The objective is to build “a binational community” that can work together to end the occupation, said Hila Aloni, a Combatants for Peace spokesperson. “The occupation separates Israelis from Palestinians. By working together, we’re disturbing and disrupting that.”

Israel’s annual Memorial Day (Yom HaZikaron) is when Combatants for Peace hosts its biggest event. Memorial Day in Israel is typically seen as a day of remembrance for Jews who died in the struggle that led to establishment of the state and in Israel’s wars since. Every year since 2005, Combatants for Peace has organized a ceremony on Memorial Day intended to acknowledge the pain and suffering of both Israelis and Palestinians. The ceremony “comes to remind us that war is not an act of fate but one of human choice,” the Combatants for Peace website says.

Every year, Israeli politicians and right-wing activists try to block the ceremony from happening, but typically about 2,000 people - including artists, actors, writers and lawmakers - turn out for the event.

In June 2016, The Jewish Independent attended the Freedom March, a Combatants for Peace event in the West Bank where 125 Israeli and Palestinian activists and former fighters marched along a highway used by settlers, in the shadow of a large concrete security wall. Participants held signs proclaiming “There is another way” and “49 years is enough,” referring to the recent anniversary of the Six Day War of 1967, when Israel began its occupation of East Jerusalem and the West Bank.

’49 (years) - enough’

’49 (years) - enough’

As demonstrators marched along the highway, some passersby were displeased. An ultra-Orthodox Jewish man driving a beat-up sedan angrily stuck up his middle finger at the crowd. But the activists barely seemed to notice. Some gave speeches on a makeshift stage, offering words of hope and praise to those who had gathered in the 33 degree heat to take a stand against the occupation, while others tied a cluster of balloons to a large cardboard cutout of Israel’s separation barrier, and let helium and the wind take it upwards until it became a tiny dot in the sky.

The march happens every month. “The purpose is to have an event where Israelis and Palestinians go out in public and demonstrate together against the occupation,” said Dean Issacharoff, a Combatants for Peace member and former Israel Defense Forces (IDF) officer from Jerusalem.

Issacharoff, 24, said he used to be “very, very nationalistic,” and that he thought it was his duty to protect Israel by serving in the army. But as a soldier in a special unit of the IDF, Issacharoff began to question whether the IDF was just protecting Israel as it claimed.

Over the course of three years serving in the occupied Palestinian Territories, Issacharoff said he came to believe that the IDF’s primary role was not to protect Israel from external threats but to police an unwilling civilian population.

For example, he said that as an IDF officer in the West Bank, he was often ordered to search houses of suspected drug dealers. He and his soldiers would enter homes in the middle of the night, rouse sleeping families from bed, line them up in the living room, take their IDs, and then scour the house for narcotics. “There’s never a warrant, and the searches are extremely violent. You raid the whole house, searching every nook and cranny for weapons and drugs or anything [illegal], and a lot of the time you find nothing,” said Issacharoff, who is tall, fluent in English, and has a scruffy, dark beard.

It was strange to be performing drug searches as a soldier, Issacharoff said. “We aren’t a drug enforcement agency. We don’t know how to raid a drug dealer’s house,” he said. “This is not supposed to be the job of a soldier. A soldier is supposed to protect the state of Israel within recognised borders. Not to control Hebron, not to police Palestinian society for fifty years.”

But more worrisome to Issacharoff was his belief that the IDF’s actions were contributing to the cycle of violence, not helping to end it. “On a tactical level, IDF raids and arrests in the occupied territories might subdue or lull the violence to a point, but on a strategic level it’s just fanning the fire.”

That’s why Issacharoff now opposes Israel’s occupation of the West Bank: because he believes that each act of violence brings the next, and that it doesn’t matter where it started. “We’re creating war and we’re creating hate, and it brings both of our societies [Israeli and Palestinian] to an abyss where we think that each side is out to kill the other.”

Dean Issacharoff in the IDF

Dean Issacharoff in the IDF

When he was released from the army last year, he started hearing through friends about former Palestinian combatants who were now agitating for their civil rights non-violently. “I’d never heard of such a thing before, but once I knew about it, I couldn’t ignore it,” he said.

A few months ago, Issacharoff became an official member of Combatants for Peace. What he, Khatib and their comrades at Combatants for Peace have in common is a belief that only when people put down their guns and start working together will peaceful coexistence be possible.

“The cycle of ‘action and reaction’ takes us nowhere,” Khatib said. “That is our message. That there is no military solution to the conflict.”

This The Jewish Independent article may be republished if acknowledged thus: ‘This article first appeared on www.thejewishindependent.com.au and is reprinted with permission.’

Comments

No comments on this article yet. Be the first to add your thoughts.