Published: 7 March 2022

Last updated: 4 March 2024

NIVA KASPI: The Fourth Window includes Galia’s claims of Oz as an abusive father but does not let the scandal dominate this portrait of the author’s life

IT WAS A film director’s worst nightmare, says director Yair Qedar. Production on the late Amos Oz documentary, The Fourth Window, had wrapped up and the film ready for distribution when a shocking biography by the author’s estranged daughter, Galia Oz, was released. Her book, Something Disguised as Love, portrays the celebrated Israeli author as an abusive, callous father.

The Israeli media flew into a frenzy, parading a daily procession of “expert witnesses”. From old school friends to child psychology scholars, all were eager to contribute to the public dissection of the Oz family. On social media, discussion forums turned into courtrooms. For a while it seemed as though the Israeli public had split into two camps; those who supported Galia, and those who sided with Galia’s mother, sister, and brother in defence of Oz.

Qedar called back the film crew - his documentary needed an update. Six months later, the film – almost three years in the making - was complete. Thankfully, Qedar resists entering a verdict on Oz’s character, striking the right balance between acknowledging Galia's painful postscript and not letting it dominate what came before.

With biography, as with any history, it is important to ask who is telling the story. Qedar opens the film with a kind of disclosure, by playing a recorded telephone conversation between Oz and his close friend, author and scholar Nurith Gertz.

Through ingenious editing, Oz seems to be responding to Galia’s accusations, even though her book was published after his death.

In this conversation, Oz asks Gertz to write his posthumous biography. He instructs her to write everything she knows, not only the good things, and even lists some unflattering suggestions. Gertz, who later went on to write the biography, provides one of the film’s central “windows” – or perspectives - into Oz’s life.

Snippets of these telephone conversations feature throughout the film, serving as meditative pauses from the otherwise chronological narrative. These intimate dialogues are played over shots taken from a Tel Aviv apartment window onto an ordinary street below.

They create an uncanny sense of Oz’s presence as a master narrator who lords over his own biography from beyond the grave. Through ingenious editing, Oz seems to be responding to Galia’s specific accusations, even though her revealing book was published well after his death.

The film constructs Oz’s biography by displaying archive footage alongside interviews with family, friends, and peers. Prominent amongst them are Oz’s friends and fellow literary heavy-weights David Grossman and AB Yehoshua. Others include former president Reuven Rivlin, and actress Natalie Portman.

Some of these appearances, Portman’s for example, seem somewhat superfluous, adding little to the story. On the other hand, Portman’s casting as Oz’s mother in the filmed adaptation of A Tale of Love and Darkness provides a rather funny punchline to the interview with Oz’s eldest daughter, Fania.

Despite offering a favourable portrait of the author, the film does not denigrate into the “song of praise” that Oz had warned Gertz against writing. Speakers talk in affectionate terms about Oz and celebrate his literary achievements, from the groundbreaking female narrator of My Michael, to the “triumph of truth” in his autobiographical A Tale of Love and Darkness.

But some also recall the critical failure of his “banal, kitsch” novel, Black Box, bemoan the author’s tendency to “subject his literary work to his ideology” and criticise his attempts to represent Mizrahi Jews in his writing.

In many of these “testimonies”, Oz’s beauty is mentioned, but not merely, as author Etgar Keret clarifies, his physical attractiveness. Keret describes Oz’s beauty as a kind of “positivity, stability and light”. The beauty of a “poster boy of a nation reborn”, he adds. It is, says Keret, what we all wanted the country to look like.

Indeed, the film links Israel's “biography” to Oz's life in a way that further accentuates his iconic status. Born a little before the formation of the State, Oz grew to become a symbol of what the young nation aspired to be.

After his mother’s suicide when he was just 12, he turns his back on his father’s urban, intellectual ways and, age 14, moves to a kibbutz. There, he learns to drive a tractor and reinvents himself as an earthy, physically capable, Sabra, albeit with a secret passion for poetry.

The 1967 war and subsequent mark the beginning of Oz’s political activism. There, too, as journalist Jonathan Freedland remarks, his charm opens many doors.

The 1967 war and subsequent occupation mark the beginning of Oz’s political activism. There, too, as journalist Jonathan Freedland remarks, his charm opens many doors, including ones that have been shut firmly to Israel’s highest-ranking politicians.

With Jewish diaspora audiences, his left-leaning views may have raised some hackles, had it not been for his capacity to woo. On one instance, Oz is seen telling authors Paul Auster and Salman Rushdie, “Tomorrow I will speak about the Israelis and Palestinians and say things which the Jewish audience of New York would not like to hear”.

To which Rushdie replies, “You are the person to say that. I’m sorry, but this is your fate”.

Oz describes himself as “a walking masquerade ball”, and one of the film’s final scenes beautifully chips at the mask. In an archive footage of Oz receiving the lucrative Israel Prize for Literature, the camera lingers on his face far longer than seems appropriate.

He gazes downwards and twitches in discomfort. In the background, the much older Oz is telling Gertz that through all those years, since his mother left him, deep down, he’s felt worthless, “and nothing can fill that hole”.

Oz is deservedly remembered as an important writer, but also as a mere human, whose life was made of both love and darkness.

In his life and beyond, Oz maintains his symbolic ties to “The Good Old Israel”, even if that Israel has become a myth, and its errors exposed and regretted. Perhaps the Galia chapter is symbolic of another phase in the Israeli experience - the rejection of the narrative of the “old guard”.

Perhaps Galia’s book has also added a necessary dimension to an overly flawless character. Oz, in this film, is deservedly remembered not only as an important writer, but also as a mere human, whose life was made of both love and darkness.

The Jewish Independent JIFF SPECIAL EVENT

On Sunday, March 13, after the 4.40pm screening of The Fourth Window at Randwick Ritz in Sydney, The Jewish Independent will present a Q&A with the film's director Yair Qedar and ABC broadcaster Geraldine Doogue. CLICK HERE to register

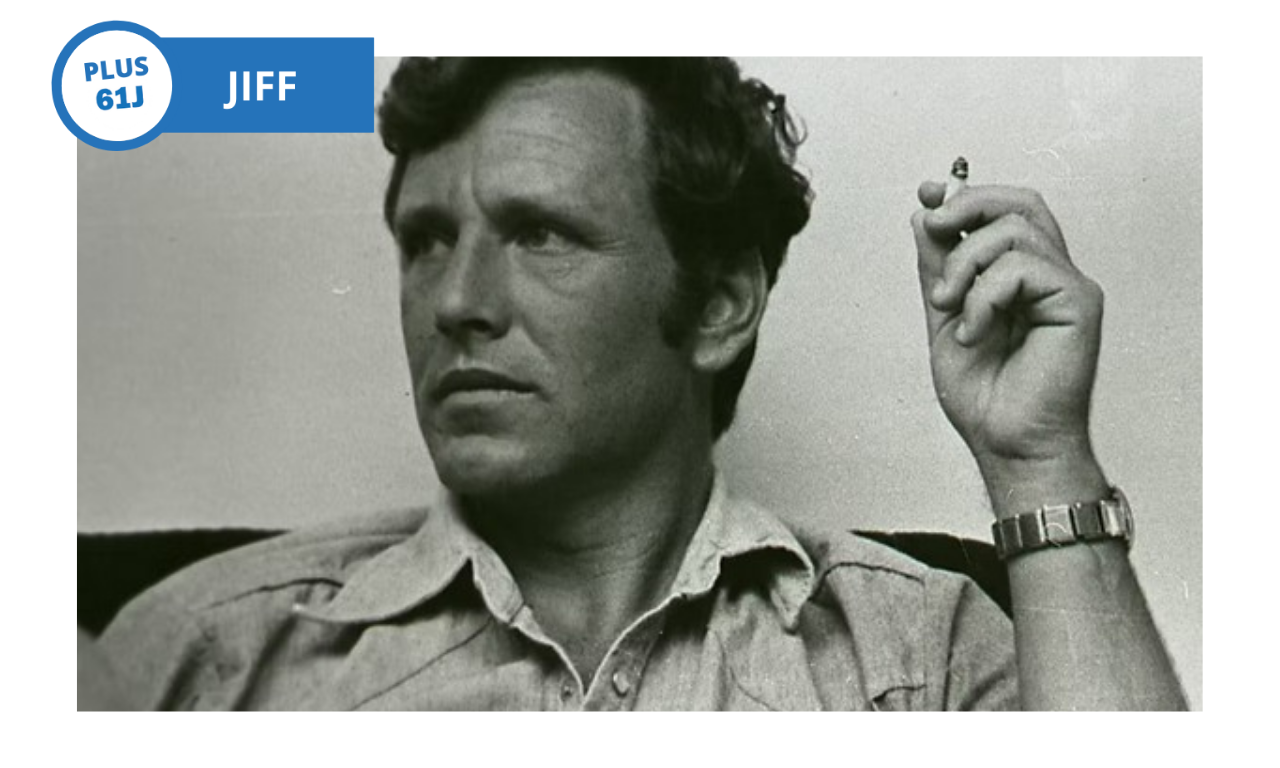

Photo: Amos Oz in a scene from The Fourth Window