Published: 14 May 2019

Last updated: 5 March 2024

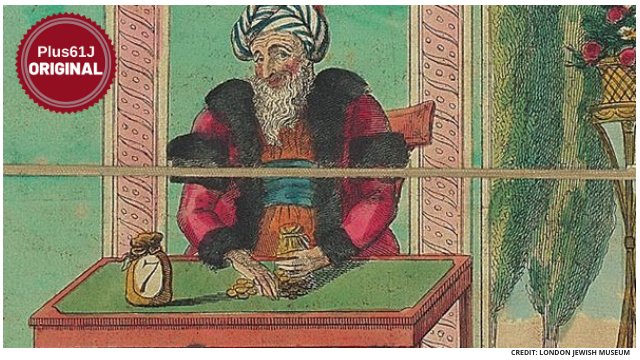

ANCIENT JUDEAN coins as an expression of Jewish resistance against Roman rule; footage of the January 1952 Israeli demonstrations against German war reparations; a cape worn by Shylock in a theatre production of The Merchant of Venice – the Jews, Money, Myth exhibition at London’s Jewish Museum is an anthropological chronicle of Jews and their relationship with money, whether real or imagined.

More often than not, this relationship is simply thrust upon them.

The exhibition, developed in collaboration with the Pears Institute for the Study of Anti-Semitism at Birkbeck, University of London, coincides with increasing concerns that anti-Semitism, and inherent stereotypes about rich, powerful Jews, is on the rise.

According to the show’s curators, “taking a step back” to provide historical context, rather than simply “chasing after the news cycle”, was key. Tropes about Jewish greed and influence that survive to this day are instead explored over 2000 years, their evolution traced over the ages, through an impressively varied and often unusual range of artefacts.

The New Testament story of Judas Iscariot betraying Jesus Christ for 30 pieces of silver and how this fuelled notions of Jewish greed is narrated with subtlety. Judas became a pejorative figure, “the archetypal traitor, a symbol of greed and heresy”, only in the 12th century, the curators note.

Exquisite artworks on display represent the Bible tale that would have such unforeseen consequences for Jews: the iconic kiss of Judas is enacted in a stunning 17th century Dutch glass panel, Betrayal of Christ, and a 12th century ivory relief from Paris, Scenes from the Passion of Christ, shows a carving of Judas receiving silver.

But it is Rembrandt’s portrayal of the Judas story, painted when he was 23 years old, that is the exhibition’s true glory. Judas Repentant, Returning the Thirty Pieces of Silver depicts Christ’s disciple on his knees, his face turned from us, wringing his hands, pleading with the Jewish priests and elders to take back the silver coins now flung before him.

The painting itself is a masterpiece of ambiguity: in many medieval images, the apostle’s robes are yellow and hair red, the iconography of treachery and deceit, but not here. Judas, who shows no distinct Semitic features, is begging on his knees, his distress clear to see. Should compassion be shown for this most vilified of historic figures, Rembrandt seems to ask.

The Middle Ages is further explored by remarkable exhibits of Anglo-Jewish life that illustrate a rich period of Jewish history little known, even in Britain.

A receipt for a debt payment, dated November 15, 1182, states that Norman landowner Richard de Malbis has paid off some of his debt to the Jew Aaron of Lincoln, one of the richest men in England. “I have received £4 from Richard the evil beast … from his debt, the large one,” Aaron’s associate Solomon has scribbled in Hebrew, a play on the nobleman’s name in French (Mal bête). De Malbis would go on to become the main instigator behind the York Massacre of 1190, described by a contemporary historian as an attempt at “sweeping away the whole [Jewish] race in their city”. The artefact is a chilling piece of history.

A hundred years after the atrocities at York, King Edward I expelled all Jews from England. Two manuscripts in the exhibition foreshadow the notorious Edict of Expulsion: one a petition written by Jews, circa 1276, informing the king of their financial hardship – the Statute of the Jewry passed the previous year placed severe restrictions on Jewish life – and asking him to clarify the statute’s details; another, a court document from 1277 about a trial involving Jews, shows the earliest surviving illustration of the “tabula” badge, a piece of yellow taffeta, shaped like the Tablets of the Law, which the statute specified Jews over the age of seven must wear above the heart.

It was only once Oliver Cromwell came to power that Jews were slowly allowed to move back to Britain in 1657. A plea by Dutch rabbi Menasseh ben Israel, writing “in behalf of the Jewifh nation”, also on display, tries to persuade England’s new leader on the subject of resettlement, emphasising the “profit” that may be derived from Jews, their “fidelity”, and “nobleness, and purity of their blood”. Jews’ reputation with money could sometimes prove a force for good, it would seem.

For the most part, however, England’s Jews were impoverished. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Jewish pedlars were common on the streets. An elaborate hawker’s licence from 1841, complete with royal warrant, is on display, proclaiming that Abraham Samuel of Reading may sell cheap goods “on foot only, without any horse, ass, mule, or any other beast, bearing or drawing burthen”; there are dainty porcelain figures in pastel shades, made between 1780 and 1820, carrying bundles of second-hand clothes to sell to the poor and growing urban population; less savoury is a 20th century Fagin-shaped nutcracker.

As for the minority of Jews who did acquire wealth, notoriety was never far behind. Nathan Mayer Rothschild, who founded the British branch of the famous banking dynasty and whose money went on to fund British military campaigns overseas, was the object of merciless caricature.

As former chairman of the Jewish Museum Alfred Rubens wrote: “Nathan was a delight with his squat, heavy figure, his coarse features, and his curious ill-fitting clothes, invariably black in figure, which retained the influence of the Frankfort (sic)ghetto.”

Indeed, perhaps the most grotesque object of all, in an exhibition replete with perverse depictions of Jews, is an 1833 sculpture of Rothschild by Jean-Pierre Dantan: a monstrous figure with demonic eyes, hunched over banknotes in an insatiable, possessed grab for money.

No exhibition of this kind would be complete without reference to the Nazi propaganda about Jews and global influence. German-issued banknotes from the Lodz Ghetto in Nazi-occupied Poland, the only money ghetto residents were permitted, have a Star of David fashioned from green barbed wire as their background. Currency from another ghetto, Theresienstadt, in occupied Czechoslovakia, depict a bearded Moses holding on to the commandments. Designed in 1943 by a Jewish inmate, the Czech writer and artist Peter Kien (who died in Auschwitz in October 1944), the banknotes were just one of many elaborate measures taken by Nazis to create the illusion of normalcy in the so-called “model” Jewish settlement.

Parallel to these gloomy artefacts and millennia-old tropes of greed, runs a refreshing counter-narrative of Jewish altruism. Sayings from the Talmud and Bible – “Charity is equivalent to all the other commandments combined”, reads one – are printed on the gallery walls, and accompany artefacts that embody tzedakah, the Jewish notion of charity: a wooden soup kitchen “tally board”’ from the soup kitchen for the Jewish poor, set up in 1854 to feed refugees from Eastern Europe; and even a Victorian “charity lottery wheel”, from the old Great Synagogue in London, which was used to draw lots when funds were insufficient to provide for all the poor.

Especially moving is a letter from the 11th century, written by a poor Jew in Cairo, in which he asks the local parnas – a community funds administrator – to help raise money for his family. “Your servant presents his supplication before the Lord and before you to act kindly with me by holding a collection for me since my wife and my children, who are due to come up from Alexandria, have written to me to say that they lack the cost of the boat ride,” reads manuscript, written in Judeo-Arabic.

This is a powerful exhibition, at an important moment in modern Jewish history, that may reflect on the past, but by no means dwells on it. In one of the last small gallery rooms, a picture of caricatured Jewish bankers playing Monopoly over the bodies of naked workers, a London graffiti work that was later removed, acts as a stark reminder of history’s long tentacles.

Jews, Money, Myth

Jewish Museum London, March 19-July 7