Published: 19 August 2022

Last updated: 5 March 2024

TAL JANNER-KLAUSNER: New letters, optional endings and switching forms are among the creative solutions to create a gender-inclusive language.

Three features of Hebrew grammar present a challenge in the context of gender justice.

Firstly, Hebrew grammar is highly gendered, with all nouns and adjectives, as well as most verb forms and prepositions, changing according to grammatical gender. It’s inescapable and strengthens the societal assumption that gender must be known, addressed and is immutable.

As the Israeli poet Yona Wallach wrote, “Hebrew is a sex maniac”.

Secondly, this grammatical gender is binary: for objects as well as people, there are only two options - masculine or feminine. Nothing neutral or other.

Finally, these two options are not on an equal footing. The masculine form often takes precedence, such as the use of masculine plural forms when addressing a mixed-gender audience, even if there is only one man present.

This is not coincidental. Language reflects our social norms and strengthens them by making them seem natural and unchangeable. For example, it can be harder to understand the concept of non-binary gender if the language you speak doesn’t seem to have an option for addressing someone who is non-binary.

Additionally, multiple research studies have shown that using masculine forms of address as default harms the achievements and motivation of women in education and work.

The movement for gender-equal Hebrew asserts that masculine grammatical gender is not neutral. This assertion is now increasingly accepted in broad swathes of Israeli society.

We are witnessing a moment of change in the Hebrew language, thanks to the efforts of the feminist and LGBTQ+ advocates. The movement for gender-equal Hebrew asserts that, contrary to the guidelines of the Academy of the Hebrew Language, masculine grammatical gender is not neutral or all-inclusive. This assertion is now increasingly accepted in broad swathes of Israeli society, widening the adoption of alternative ways of speaking and writing.

In speech, many people now refer to mixed-gender groups using both feminine and masculine forms; they alternate between the two forms; align with the majority present, or find alternative ways of addressing a specific group.

For example, instead of מורים (teachers – masculine plural) you might hear מורים ומורות (masculine and feminine plural) or צוות הוראה (educational team – a phrase without gender).

In writing, popular strategies to include all genders in one word include inserting full stops (דרוש.ה עובד.ת), a forward slash (דרוש/ה עובד/ת) or a double ending (חבריםות, חברותים).

These adjustments have been criticised as visually convoluted, and gender-inclusive style guides recommend, where possible, using language that includes all genders without the need for such additions.

Luckily there are many ways to do so: making use of infinitive verbs, verbal nouns, and forms which, without vowel markings (nikud), could be read as either masculine or feminine (for example: שלך, רוצה, אמרת).

Another elegant solution for written Hebrew is the use of multi-gender Hebrew (עברית רב מגדרית). Developed by designer Michal Shomer, these are additional letters which produce a visual combination of the masculine and feminine forms to address all genders. Multi-gender Hebrew is now widespread, and is used, for example, in welcome signs to schools.

In recent years, these different forms of inclusive Hebrew can be seen and heard in such mainstream contexts as advertisements on public transport; politicians’ speeches across the political spectrum; letters from healthcare providers; social media accounts of city municipalities, and more.

The Academy of the Hebrew language has established a committee dedicated to gender issues in Hebrew and is well aware of the increasing public pressure for an unsexist useage.

However, official take-up has been held back by the legal requirement for government institutions to comply with the standards set by the Academy for the Hebrew Language. However, the Academy for the Hebrew Language often responds to how Hebrew is used in practice, recognising that language is not a fixed entity.

This means there is room for cautious optimism: the Academy has established a committee dedicated to gender issues in Hebrew and is well aware of the increasing public pressure for an unsexist useage.

With regards to expression of non-binary gender, the road seems more challenging, given the binary nature of Hebrew. While written solutions are in use, they cannot be expressed in speech.

In Israel, many non-binary people use “mixed address” לשון מעורבת – switching between masculine and feminine forms. Others use either masculine or feminine, whilst recognising that grammatical gender need not define their gender identity.

For many, both of these options feel inadequate or uncomfortable. Hence, there have been attempts to develop novel gender-neutral grammatical structures, as has occurred in other binary-gendered languages such as French and Spanish.

The most systematic of these innovations so far are the “gender expansive” grammatical forms of “The Non-binary Hebrew Project”. Based in the US, this project is gaining popularity for use in liturgical and other Jewish communal contexts in communities around the world but is not currently used or well-known among the non-binary community in Israel.

Some users of non-binary Hebrew have voiced concerns that this may distance Diaspora Hebrew from Israeli vernacular Hebrew. However, Hebrew has always had many different dialects and uses.

Whether using mixed address or novel forms, non-binary speakers of Hebrew can be encouraged by the recent successes of gender-equal Hebrew. It is a reminder of the necessity of experimenting with different options, and a demonstration of how quickly language can develop when society understands the need for change.

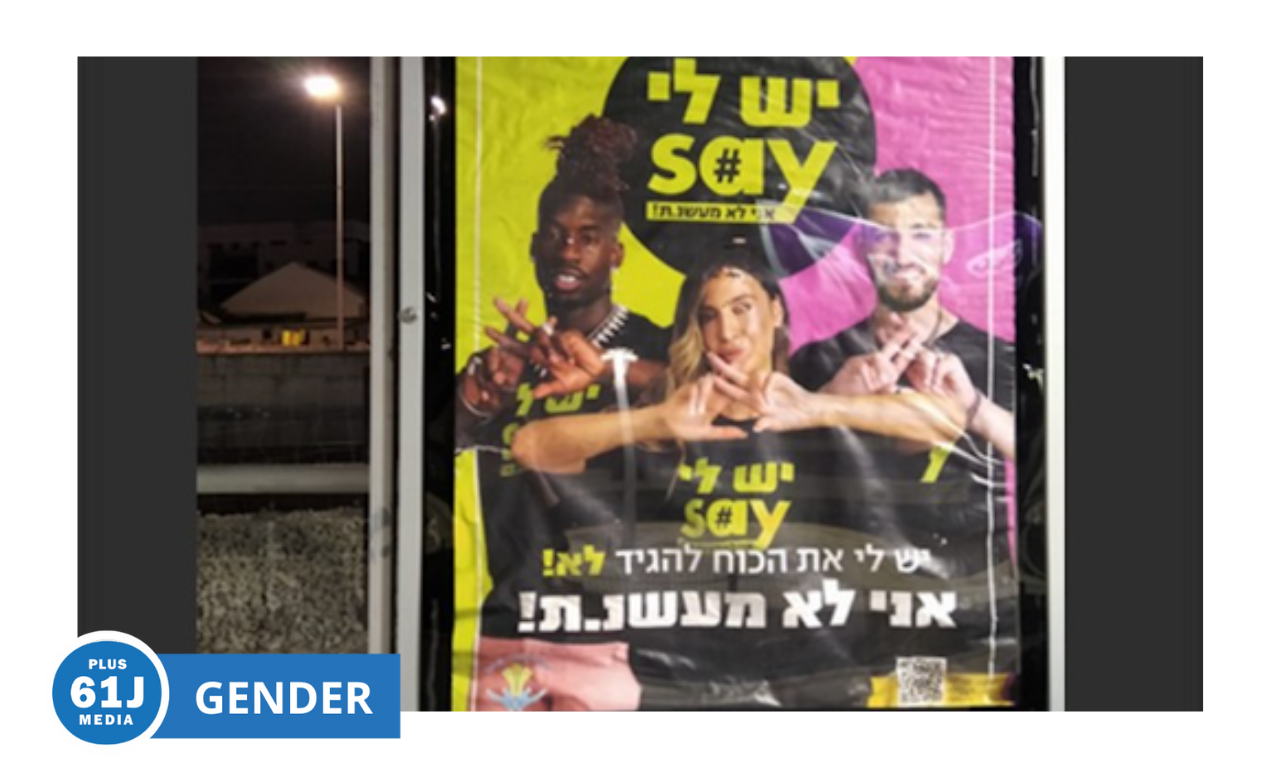

Photo: Advertisement from a railway platform in Israel: ‘I have the power to say no! I don’t smoke!’ “Smoke” is written in mixed-gender Hebrew, with a full stop separating the masculine and feminine forms (The Branded Content Agency)