Published: 3 June 2017

Last updated: 4 March 2024

Fresh out of high school in Johannesburg, South Africa, the 17-year-old Feinstein, first boarded a plane to Europe with his parents.

“They were going to Europe and London, so we parted company in Rome,” he recalls. “I was put on a plane to Israel and was met by members of the South African Zionist Federation when I arrived.”

Feinstein came from a long line of Lithuanian Jews who had settled in South Africa and his father was chairman of the local synagogue at the time. He recalls having a traditional Jewish upbringing, despite the occasional oddity. “On Friday night we always had a kosher dinner, then on Sundays we’d go out and eat seafood that included prawns. My father also used to preach progressive policies, voted middle of the road, and proceeded to thank God that the National Party was in government.”

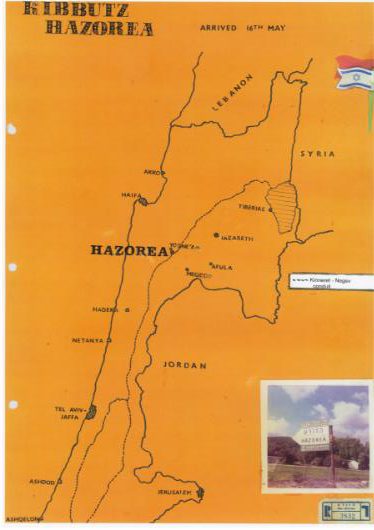

On 7 May, he arrived at Kibbutz Hazorea (population 1,300), alongside Yoqne’am, in the Jezreel Valley in the north. Founded in 1936, it is the only Kibbutz established by the German Werkleute movement.

“My parents sent me there to go to the Ulpan to learn Hebrew, with the hope that I might actually settle in Israel,” Feinstein says. Shortly after his arrival, however, tensions began rising between Israel and its neighbours to the south, east and north – namely Egypt, Jordan and Syria.

On 30 May, a pact between Egypt and Jordan was concluded and Kibbutz Nahal Oz in the south was fired on from Gaza.

Meanwhile, Egypt, Syria and Jordan had gained the support of a host of other Arab nations including Iraq, Kuwait, Lebanon, Algeria and Morocco and were once again collectively discussing the possibility of wiping Israel off the face of the earth, egged on by Egypt’s pan-Arab nationalist leader Gamal Abdel Nasser.

On 19 May, the day after the United Nations pulled their troops out of the Sinai and the Egyptians moved in, Feinstein was fortunate enough to attend the Independence Day parade in Jerusalem. Four days later Nasser closed the Straits of Tiran, the narrow sea passage between the Sinai and Arabian peninsulas that was vital for Israeli shipping.

“One Saturday morning in May, three Americans and I went off to Nazareth, got back to the kibbutz and found everyone digging trenches,” Feinstein recalls. “They ended up encircling the entire kibbutz. For the rest of May, we continued filling sandbags for defensive positions and the kibbutz was blackened out at night.

“At the same time, Arab radio, which we could easily pick up, announced ‘run Zionists run’, which caused a mass exodus of foreigners from the kibbutz. All in all, between 70 and 80 per cent left, which was typical of most foreign Kibbutz-Ulpan populations at the time. Some of us, however, decided to stay. My parents, who were in London at the time, kept sending me telegrams to leave, but I assured them that everything was fine.”

Before the war started, Israel had been actively looking for volunteers and was also encouraging foreigners to stay. Feinstein tried to join the IDF but was told that foreigners could not join for political reasons, though he insists that his age would not have been a barrier at the time.

Ironically, by leaving South Africa when he did, Feinstein was able to avoid a compulsory call up that would have seen him fighting in a war against Angola for control of the Caprivi Strip that bordered the two countries, something which he had absolutely no interest in taking part in.

On June 2 Moshe Dayan was appointed Israeli Defence Minister, the Egyptian army continued to mass in the Sinai, the Jordanians took up positions in the West Bank and the Syrians moved into the Golan Heights.

“Everyone in the kibbutz was giving blood,” Feinstein says.

“The kibbutzniks had already been called up as reservists and those of us who had stayed were left to ‘defend’ the kibbutz. We were given rifles with no firing pins in them and no ammunition.”

On 5 June, the day after the final pact between Egypt and Iraq, the war began, with the Israelis launching pre-emptive strikes that obliterated the collective air forces of Egypt, Syria and Jordan.

“From Hazarea, we were able to climb up a huge silo on the first night of the war, where we could see the firing from the distance. On the second night, however, we could hear but no longer see any fighting because the Israelis had pushed the enemy so far back already. For a 17-year-old it was incredibly exciting.”

And it was very fast. By June 11, a ceasefire was signed and it was all over: in one of the most decisive military victories of the 20th century, the Israelis had retaken the Sinai Peninsula from Egypt, the West Bank from Jordan and the Golan Heights from Syria.

Says Feinstein: “The war finished very quickly, the Ulpan restarted and in the end the kibbutzniks were only gone for a couple of weeks.”

The quick victory and the annexation of conquered territory meant Feinstein was now free to travel to areas that had earlier not been possible, and two months later he visited the West Bank.

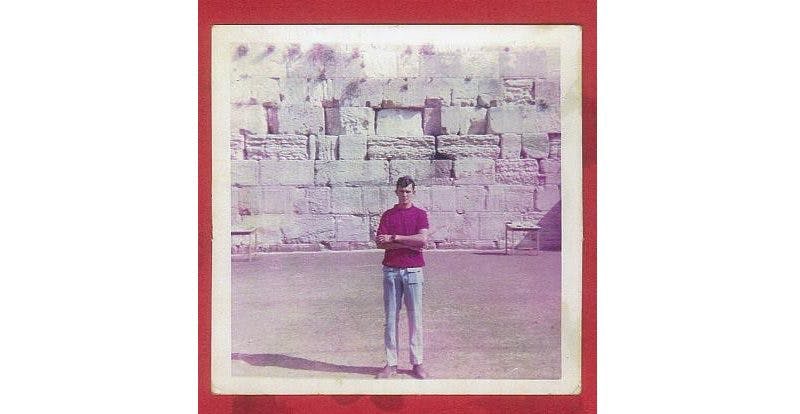

“I was quite agnostic from a religious point of view when I arrived in Israel, but when the soldiers came back from Jerusalem and told us about how they had touched the Western Wall and it had changed their spiritual beliefs, I decided I had to see and touch for myself. I went to the wall - and nothing happened, so I became a confirmed atheist then and there.”

He also went to the Golan Heights, climbed aboard captured tanks and visited the Sinai, where he saw “hundreds of bank notes in Arabic scattered on the streets”.

On 13 October, the residents of Hazarea began filling up the trenches, which he recalls thinking at the time was “optimistic”. After spending six months on Hazarea, from May to October, Feinstein went to kibbutz Sde Yoav in the Negev.

“The kibbutz had a population of 47 and one foreigner. Not one other person spoke English, the buildings were shacks, and I got to drive caterpillars and trucks. I was also put in charge of the artichokes and gladioli. Before that, on 2 November, I got to walk around Gaza where I felt totally safe, but maybe that was just my naivety.”

Towards the end of his stay, Feinstein once again got to see the Independence Day celebration in Jerusalem, which this time around was a true victory celebration, unlike the previous year’s parade, which had attempted to send a message of confidence.

“There were planes flying in Magen David formation and a MIG-21, courtesy of an Iraqi pilot who had surrendered to the IDF in 1966.”

During the parade guards stood on all the buildings expecting trouble. Thirteen Arabs were killed trying to enter Israel on the same day, a bomb was found under one of the parade grandstands and all planes that were used for the parade were fully armed.

Feinstein left Israel on 27 May 1968, then spent time in Europe, Fiji, the US, Canada and in his native South Africa. He eventually settled in Australia in 1972, which he has happily called home ever since. He helps Muslim refugees in Australia with his volunteer program Music for Refugees.

This The Jewish Independent article may be republished with this acknowledgement: “Reprinted with permission from www.thejewishindependent.com.au”

Comments

No comments on this article yet. Be the first to add your thoughts.