Published: 1 February 2021

Last updated: 4 March 2024

MANY JEWS WILL HAVE been understandably relieved to read that a new retelling of Shakespearian stories for children will omit The Merchant of Venice.

My feelings are more mixed.

Of course, no Jew and no one else with any sensitivity feels comfortable with this most notorious tale: on key dimensions it is appalling. The anti-Semitic stereotyping of Shylock cannot be purged and any revival of the unyielding usurer ready to cut a pound of flesh from the merchant unable to pay his debt perpetuates an image of Jews as grasping, rich and unscrupulous outsiders.

But The Merchant of Venice is also, in many ways, an excellent play. It includes two of Shakespeare’s finest speeches and, skillfully interpreted, it showcases the psychological depth and continuing relevance of Shakespeare.

Recent productions, some of them starring Jewish actors, have grappled with its dark side and delivered insightful interpretations that are a valuable contribution to our cultural discourse.

Sir Michael Morpurgo’s forthcoming Tales from Shakespeare retells the stories of 10 Shakespeare plays for the contemporary young reader. It is a selection and, on that criterion alone, leaving out The Merchant is justified. The play is certainly not a consistent selection in lists of Shakespeare’s Top Ten, although when Time Out surveyed British audiences for their votes on The Bard’s best, it squeaked in at number 10.

Morpurgo children’s tales, by definition, will offer a pared-down starter Shakespeare so it makes sense to avoid complexities that cannot be appropriately contextualised.

The best interpretations explore the psychology that created Shylock with an understanding of Jewish history. They make his flaws a response to both his personal suffering and the persecution he has experienced as a Jew

But that’s because it’s kids’ stuff. We should not consider the decision to exclude The Merchant from a children’s selection as any kind of endorsement that the play should be off the agenda for production nor off the syllabus for study by senior students.

I know it’s hard to hear. My mother was the only Jew in a high school class that studied it in the 1950s. Seventy years later, she still shrinks at the humiliation and remembers wanting to disappear beneath the floorboards as other students learned to equate the word “Jew” with miser, usurer and villain.

I’ve had a decent Shakespeare education but I never studied The Merchant at school or university. My father avoided the risk that his children might suffer the same discomfort by using parent-teacher meetings to argue the case for Twelfth Night or Midsummer Night’s Dream as introductory Shakespeare in place of The Merchant.

I suspect he was sufficiently intimidating that our English teachers were too scared to take the risk of dealing with Shylock, knowing he would be watching for their handling of the antisemitism.

But as an adult I’ve gone out of my way to encounter The Merchant of Venice and its response texts and I am strongly opposed to it being excised from the canon. It’s an interesting play with a great deal to say about capitalism, justice and gender politics – though most of us are too upset by the way it talks about Jews to notice.

In the age of cancel culture, it is too easy to lose swathes of our cultural history while taking justifiable offence at particular aspects of a work (and sometimes at a single comment by an author or artist that is not even directly relevant to the work).

Reviving Shylock is an exercise in creative interpretation. Modern productions drop the hooked noses and red wigs, which signified a Jew to Elizabethan audiences. Some try to keep the Jewish referencing to a minimum.

But the best of them, in my opinion, explore the psychology that created Shylock with an understanding of Jewish history. Rather than deracinating him, they make his flaws a response to both his personal suffering and the persecution he has experienced as a Jew.

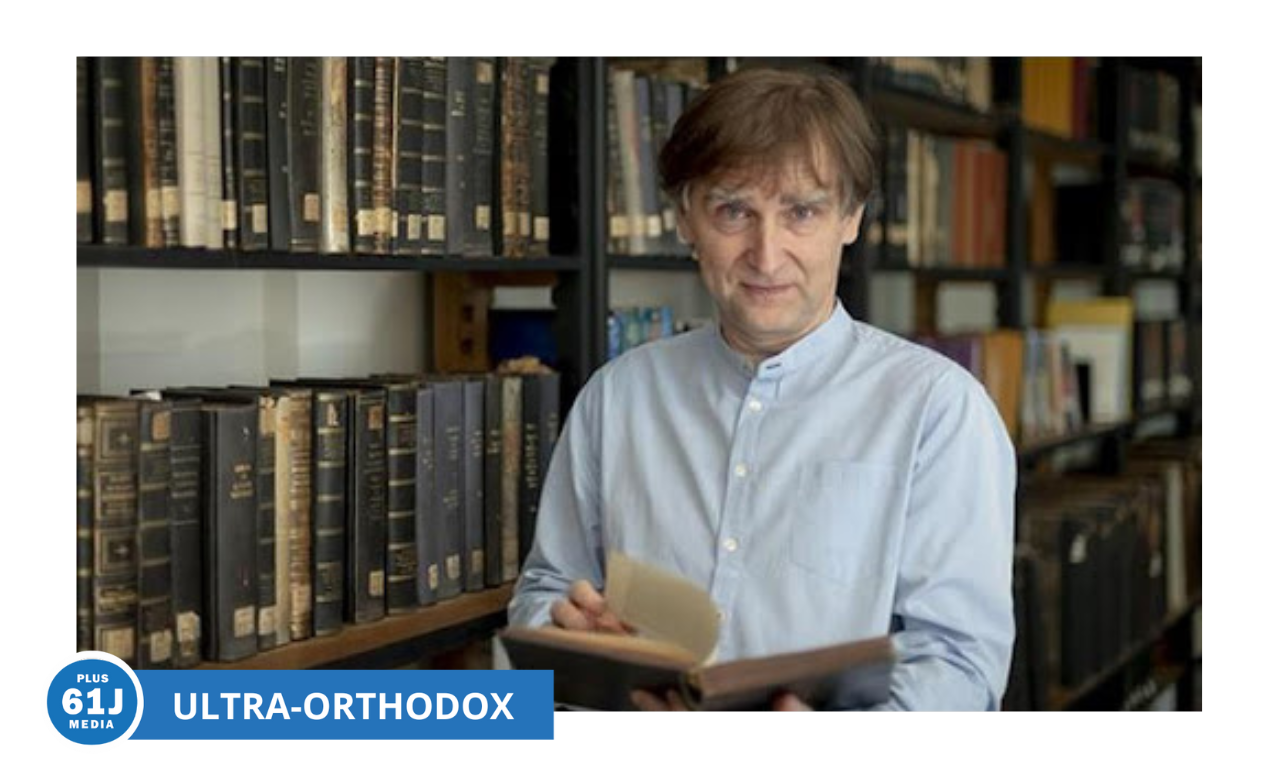

The 1980 film by (Jewish) director Jack Gold, with (Jewish) actor Warren Mitchell in the role of Shylock is my personal favourite. Mitchell was best known as loud-mouthed Cockney bigot Alf Garnett in the TV comedy Till Death Us Do Part and he brings the same cheek and bluster to his Shylock.

I am strongly opposed to it being excised from the canon. It’s an interesting play with a great deal to say about capitalism, justice and gender politics – though most of us are too upset by the way it talks about Jews to notice

The result is an interpretation which emphasises class and the power of capital, as small-statured, fast-talking upstart Shylock encounters the born-to-rule merchant and his old-money friends. If we can stop being anxious long enough to see it, we might recognise the loud, nouveau riche Shylock and read his social exclusion with contemporary eyes.

Laurence Olivier, in the classic 1973 film, revealed Shylock as a wounded beast. His Shylock is a sensitive and damaged soul whose insistence on his pound of flesh from the ruined merchant Antonio comes to him in a mad flash of grief.

Italian American Al Pacino created an angry embittered but perhaps overly sanitised Shylock in the sumptuous 2004 version.

More powerful to my mind, was the 2017 Bell Shakespeare production starring Mitchell Butel as a hauntingly beautiful and tragic Shylock in a stark modern production that focused on the great divisions of wealth, culture and religion.

Shylock lives and he continues to speak – both in Shakespeare’s words and in new voices. Howard Jacobson interrogated the play through his novel Shylock is My Name which brings the character into the 21st Century with Jacobson’s trademark mixture of wit, crudity, bad puns and sharp insights.

Shakespeare may be rolling in his grave but it doesn’t matter. The Merchant of Venice is part of our heritage. It is ours to interpret, retell and mash-up but it is not ours to discard.

Photo: Warren Mitchell as Shylock in the 1980 film directed by Jack Gold