Published: 25 June 2017

Last updated: 4 March 2024

Jibril Rajoub, a former security chief in the West Bank and serious contender for the position, was first arrested by the IDF at 15. He spent most of his teenage years in and out of Israeli jails, where he learned Hebrew and studied Zionist history, even translating Menachem Begin’s The Revolt into Arabic. Mohammed Dahlan, once Yasser Arafat’s strongman in Gaza and now Abbas’s nemesis, was arrested 11 times as a teenager in the 1980s, gaining fluency in Hebrew within the prison walls. Marwan Barghouti, perhaps the greatest symbol of the prisoner struggle against Israel and also a contender to succeed Abbas, is serving five life sentences for his involvement in terrorism during the Second Intifada.

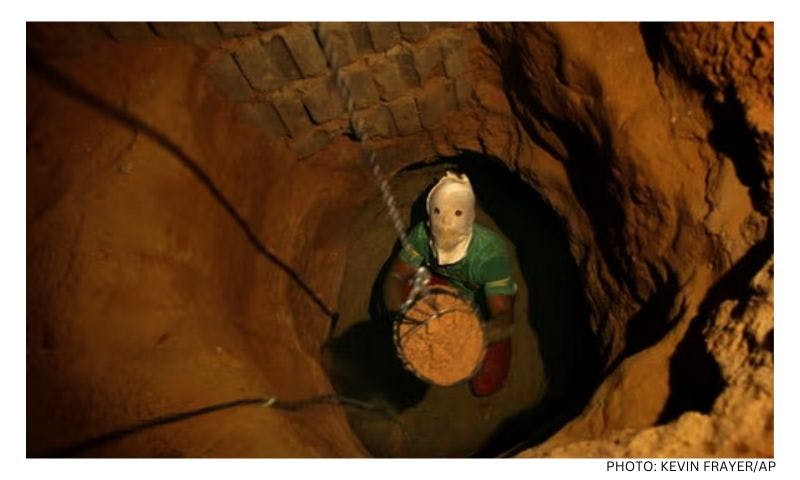

A staggering 800,000 Palestinians have passed through Israeli jails since Israel’s occupation of the West Bank and Gaza Strip 50 years ago, according to data collected recently by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. Even if slightly exaggerated, those numbers make it highly likely that every Palestinian family is closely acquainted with at least one prisoner or ex-prisoner. And Israeli prisons do not serve solely as punitive institutions; they are effectively leadership-training academies of Palestinian society.

But the Palestinian prisoner movement has now reached a crossroads. According to research by Dr Maya Rosenfeld, it has lost its primacy in leading the national struggle due to a number of factors - the abandonment of armed struggle by Fatah in the West Bank (though not by Hamas); increased bureaucratisation of Palestinian politics and expansion of the public sector, where employees are bound by the current PA policy of non-violence; and the proliferation of higher education.

A panel discussion titled The Palestinian Prisoners’ Movement 1967-2017 took place last week at Hebrew University’s Harry S. Truman Research Institute for the Advancement of Peace, showcasing Dr Rosenfeld’s research. The panel had originally been planned for mid-May, but was then postponed for what were said to be ‘logistical’ reasons, after right-wing organisations on campus protested against the invitation of ex-prisoners now associated with al-Quds University.

The panel speakers were Dr Rosenfeld, former PA Prisoner Affairs minister Ashraf al-Ajrami, Radhi Jara'i of the Abu Jihad Center for Prisoner Affairs at al-Quds University and Dr Fahed Abul Haj, director of the Abu Jihad Center at al-Quds University. The format of the event had not changed since it was advertised in May and some attendees wondered aloud why right-wing students were not protesting again. Panel chair Dr Roni Shaked remarked that al-Quds University had boycotted the Hebrew University and the Truman Institute for the past two years and that policy seemed now to have changed.

Rosenfeld and her research team interviewed numerous ex-prisoners, documenting the rise and fall of the prisoner movement as the flagship of the Palestinian national liberation struggle from the early 1970s to the present.

The most significant prisoner hunger strike in recent years, a 40-day protest led by Barghouti and the Fatah movement, ended on 27 May this year with a whimper, not a bang. Rosenfeld posed the question: Have the security prisoners, once the vanguard of Palestinian society, lost their primacy as a driving force for Palestinian politics?

She mapped out three main periods in the history of the prisoner struggle. From 1967 to 1993 thousands of prisoners were jailed by Israel, which fully controlled the entire West Bank. That’s when the prisoner movement took root and expanded. From the signing of the Oslo Accords in September 1993 to the outbreak of the Second Intifada in October 2000 some 10,000 Palestinians were released from jail, many of them receiving positions as civil servants in the newly created Palestinian Authority. Finally, the period from the Second Intifada to the present marks the collapse of the Oslo process and the optimism it carried, with the return of mass arrests. Today some 6,500 Palestinians are incarcerated in Israeli prisons.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Rosenfeld noted, almost all prisoners belonged to political movements and remained associated in prison with their political group and subject to its elected leadership. Daily political meetings would take place in prison, where leaders discussed matters of policy within the prison and outside. Inmates went through a rigorous education process they had often been deprived of growing up, studying Hebrew and the history of both the Zionist movement and the Palestinian national movement, as well as general academic studies and rhetorical skills. Fatah leaders in jail would receive their orders from party leaders based in Lebanon, and later in Tunisia.

The establishment of the PA in 1993 depleted the numbers of prisoners in Israel jails and turned many ex-prisoners into bureaucrats employed in government offices or the various PA security agencies. The Ministry of Prisoner Affairs and the Palestinian Prisoner’s Club were established to rehabilitate ex-prisoners released during the early years of Olso.

The Second Intifada marked a reversal in that trend. Thousands of Palestinians active in fighting the Israeli occupation returned to jail, their number reaching as high as 9,600 in 2006. In recent years numbers have fluctuated between 4,500 and 7,000.

But despite the increase in arrests, and the return to centre stage of the prison experience in Palestinian life, Rosenfeld said the collective prisoner movement has lost traction in Palestinian society.

“The prison has stopped being the main arena of Palestinian struggle for independence,” Rosenfeld said. “It’s as though they’ve returned to square one. Can today’s prisoners serve as the basis for a new struggle? I doubt it. The leadership doesn’t support that.” Rosenfeld added that Palestinian public discourse does not cite these reasons for the dwindling of the national movement, only the political divide between Fatah and Hamas.

Ashraf al-Ajrami, a former prisoner who served as PA Minister of Prisoner Affairs between 2007 and 2009, said the harsh conditions in Israeli prisons helped unite prisoners and consolidate their movement.

“Prisoners gained all of their achievement through [hunger] strikes,” he said, adding that Palestinians were especially inspired by striking IRA prisoners in British prisons. “It was the only way to achieve better, more humane conditions in prison.”

This The Jewish Independent article may be republished with this acknowledgement: ‘Reprinted with permission from www.thejewishindependent.com.au ’

And see:

Abbas defends payments to convicted terrorists as ‘social responsibility’ – Dov Lieber – The Times of Israel 22.06.17

PA president accuses Netanyahu of using issue of ‘incitement’ as pretext to avoid serious negotiations. Reiterates call for revival of the tripartite Israeli-American-Palestinian committee on incitement.

PA set to dissolving Palestinian Committee of Prisoners’ Affairs – Middle East Monitor 19.06.17

Under pressure from the US and Israel, the Palestinian Authority is said to be considering dissolving the Palestinian Committee of Prisoners’ Affairs.

Related:

Prisoners, peace and the Palestinian national movement

Who’s a ‘terrorist’, who a ‘freedom fighter’?

Prisoners’ hunger strike reportedly ended after 40 days

For a previous publication by Hebrew University sociologist Dr Maya Rosenfeld on Palestinian society in the occupied territories see here.

Comments

No comments on this article yet. Be the first to add your thoughts.