Published: 23 April 2017

Last updated: 4 March 2024

In 1913 Keysor departed Canada to join his brother Stanley and sister Madge, who had moved to Australia. When war broke out, Keysor was working as a clerk in Sydney. He was among the first 1000 men to enlist in the 1st Battalion AIF. When he entered the army, he took the precaution of knocking a year off his age (he enlisted as twenty-seven when he was actually twenty-eight) and the social shackles off his religion. He proclaimed his faith as ‘Church of England’, although he was openly Jewish thereafter.

Keysor sailed from Sydney on HMAT Africa as a private soldier with H Company, 1st Battalion, 1st Division AIF and landed at Gallipoli on 25 April. In August 1915, already an expert bomb-thrower with a bowler’s arm, Keysor was battling through the maelstrom of Lone Pine. The Turks showered the Australians with cast-iron hand grenades which – as has often been pointed out – were a similar size to cricket balls. Keysor stood among the bombs as they rained down, and replied to the barrage with improvised Australian ‘jam-tin’ grenades. ‘He generally carried on his job from a raised platform in the side of the trench,’ wrote a comrade. ‘His “jam-tin” bombs always drew a response from the Turks, but Keysor seemed to bear a charmed life, and he did not know the meaning of fear.’

On 7 August, according to Keysor’s citation for the VC, he was in a trench under heavy bombardment by the Turks when he ‘picked up two live bombs and threw them back at the enemy at great risk to his own life, and continued throwing bombs, although himself wounded, thereby saving a portion of the trench which it was most important to hold.’ The next day the wounded Keysor ‘successfully bombed the enemy out of a position from which a temporary mastery of his own trench had been obtained, and was again wounded. Although marked for hospital he declined to leave, and volunteered to throw bombs for another company which had lost its bomb-throwers. He continued to bomb the enemy till the situation was relieved.’

He wrote home to his sister Madge, ‘My word, it was a grand affair, but, unfortunately, there was a terrible lot of casualties. I had a slight cut on the mouth.’ His Jewishness was immediately acknowledged. His mother told the press, ‘As a co religionist I should have been proud of him – but my own son – well, it’s simply glorious.’

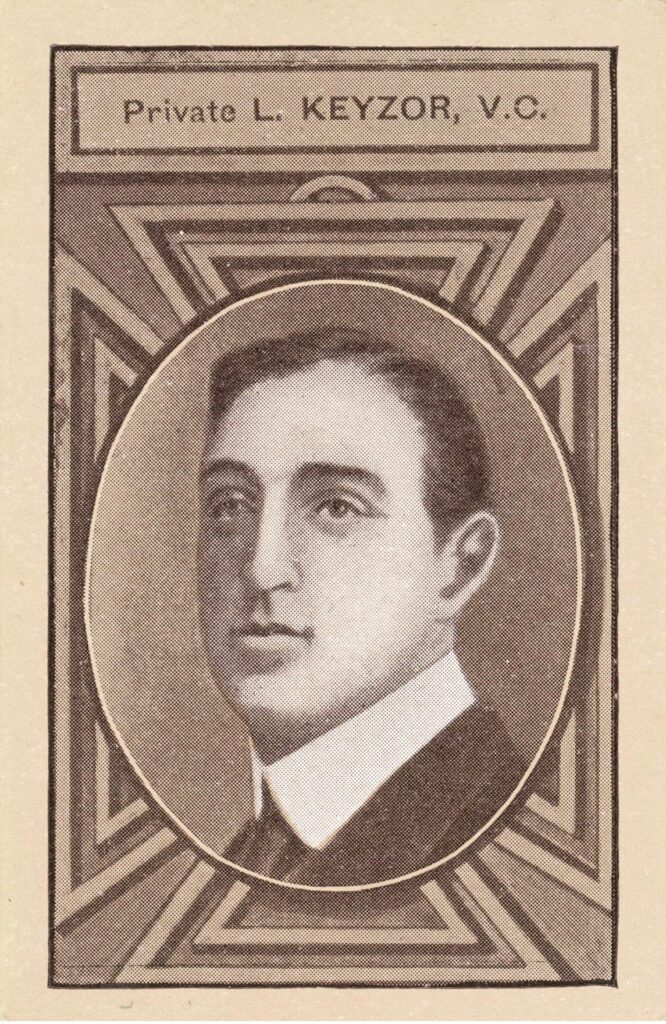

With only a brief passage of time, Keysor’s deeds became exaggerated, and the Imperial idol – whose dark Semitic features watched schoolboys and housewives from cigarette cards and biscuit tins – grew from hero to superhero. According to the book Deeds that Thrill the Empire he ‘not only hurled our bombs at the enemy, but managed to cover with overcoats and sandbags the bombs which the enemy threw at us. Others he caught in their flight without letting them explode.’

The men at the time were unconvinced. One Frank Lesnie, a London-born Jew in the trenches with the AIF, wrote home, ‘You might have read that a favourite trick here is to catch the Turkish bombs, throw them back again and so hoist them with their own petards. A spectator would think and witness otherwise. The moment a bomb is seen to drop over the parapet, there is a muddy rush for the four corners of the globe; so much so, that one trench is called by the name of “The Racecourse”.’

[caption id="attachment_10206" align="alignnone" width="666"]

Sinders & Abrahams Tobacco cigarette card honouring Leonard Keysor VC[/caption]

Sinders & Abrahams Tobacco cigarette card honouring Leonard Keysor VC[/caption]But Keysor’s feat of grenade-catching – which appears never to have been claimed by Keysor himself – was already orthodoxy when a Russian journalist sought out the AIF to visit the hut where lived ‘the greatest wonder of the whole Australian camp – the famous, wonderful Keysor, about whom I had read so much, whose portrait I had seen in shop windows and on sweet boxes. Keysor, who had been so much praised in the papers. But, good heavens, is this he? A small, weak, plain man, not at all like a hero. Is this the man who for fifty hours on end protected his comrades from the Turkish hand grenades, catching them and throwing them back, like children’s tennis balls? ... I looked at his face, which was not young, at the long, winding line of his mouth, and in a moment it struck me: “Listen, you are a Jew, aren’t you?” He smiled an ancient Jewish smile. His features were sharp and frowning. A typical youth of Odessa. He treats himself sometimes ironically, sometimes with the greatest respect, triumphantly. “Yes, we are Jews from Persia.”’

The journalist asked Keysor to talk about his deeds, but he modestly refused. ‘He shook his head lazily. “It isn’t worthwhile. I have so often told the story. And, besides, what did I do in particular? Others were doing more, only no one saw them, whereas they happened to notice me.”’ On prompting, Keysor showed the Russian his VC, ‘the rarest distinction in the world’. The journalist marvelled, ‘The King himself receives him at his palace, the papers publish his biography, his figure in wax is set up in Madame Tussaud’s Museum, and the crowd that meets him in the street greets him.’

[caption id="attachment_10209" align="aligncenter" width="702"]

Australian, British and American soldiers at Passover Seder at YMCA’s Jewish Hut, April 1919[/caption]

Australian, British and American soldiers at Passover Seder at YMCA’s Jewish Hut, April 1919[/caption]Keysor was the AIF’s first Jewish VC, but two other Jewish VCs of World War One also had Australian connections and one of them, the Egyptian-born Issy Smith, is widely claimed as Australian (as well as British but never, it could be noted, as Egyptian).

The first Jewish VC of the war was Sudan veteran Ernest Simeon de Pass’s younger cousin, Frank Alexander de Pass, who died near Festubert, France, on 15 November 1914. Frank, born in England, had graduated from the Royal Military College Woolwich and transferred to the Indian army. It was as a lieutenant in the 34th Prince Albert Victor’s Own Poona Horse that Frank displayed ‘conspicuous bravery’ in ‘entering a German sap and destroying a traverse in the face of the enemy’s bombs, and for subsequently rescuing, under heavy fire, a wounded man who was lying exposed in the open’. Dryly, the citation continues, ‘Lieutenant de Pass lost his life on this day in a second attempt to capture the aforementioned sap, which had been re-occupied by the enemy.’

De Pass was awarded his medal the following year, and his story became celebrated in Australia. The sacrifice was linked explicitly with the cause of the Jewish people, by the Jewish and secular press alike. The Perth Sunday Times predicted, ‘This young soldier’s heroism will not soon be forgotten, and neither will the honourable part which the Jewish community is playing in the war. There are only a quarter of a million Jews in the United Kingdom, and many of them are men of alien birth, who are not eligible to wear the King’s uniform, yet no fewer than 10000 Jews are serving in the British Army and Navy. In proportion to the number of able bodied males capable of bearing arms, none of the composite communities which make up the British Empire have a better record than the Jews.’ A letter from Frank’s father Elliot, written to a friend in New Zealand, was published in the Hebrew Standard.

Even in grief, Elliot de Pass related the sacrifice of his son to the fight against antisemitism. ‘Whilst we weep in the privacy of our home, we neither repine nor show any lack of courage to the world,’ he wrote. His consolation was the thought that his son’s VC might ‘help to lessen the prejudice against his race, that [it] is obsessed by the love of gain, that care little for the more immortal virtues, and value their lives more than their country’s weal’.

This is an edited extract from Mark Dapin’s Jewish Anzacs: Jews in the Australian Military, NewSouth Publishing, April 2017, AUD$39.99.

Comments

No comments on this article yet. Be the first to add your thoughts.