Published: 3 June 2017

Last updated: 4 March 2024

The song was played at the festival in Jerusalem on the night of Independence Day on 15 May 1967. It was an instant hit, and a lasting one: the timing - barely three weeks before the Six-Day War and victory in Jerusalem - was propitious for Shemer, conferring iconic glory on the song. But less well-known is the story of another song, written at much the same time by a shell-shocked paratrooper, called Jerusalem of Iron. Gritty and anguished, the song is the darker flip side of Shemer’s golden coin. The two songs signify competing narratives about the war, the Palestinian territories and the border between memory and myth.

The first stanza of Shemer’s Jerusalem of Gold describes the desire to return to the Jerusalem of old, alluding to Jeremiah’s description of the city in the opening verse of the Book of Lamentations.

The mountain air is clear as wine

the scent of pines

is carried by the afternoon wind with the sound of bells,

in the tree’s sleep and with the stone lost in its dream

the city that lay so deserted,

and in its heart a wall

Chorus:Jerusalem of gold, of copper, and of light;

For all of your songs, let me be your lyre.

The following two stanzas continue the theme, lamenting the Old City’s dry cisterns, the silence on Temple Mount and the deserted marketplaces. The song ends with a reference to Psalm 137:

Your name burns my lips like the bite of a viper

If I forget you, Jerusalem, which is made purely of gold.

On the day of the song festival the Egyptian army crossed the Suez Canal into the Sinai. The IDF drafted reservists. The country prepared for war. As the tension mounted, Jerusalem of Gold grew more popular, both on the battle fronts and on the home front. Radio broadcasts of soldiers singing the song formed part of the soundtrack every day.

After three weeks the waiting game ended and the Six-Day War erupted. When Israeli paratroopers reached the Old City of Jerusalem, the Temple Mount and the Western Wall they sang the song.

Immediately after the war Shemer added another stanza celebrating the new status of the Eternal City:

We’ve returned to the water cisterns, the market and to the plazas,

A ram’s horn calls us from the Temple Mount in the Old City

And in the mountains’ caves thousands of suns are shining

Once again, to Jericho we will descend via the Dead Sea.

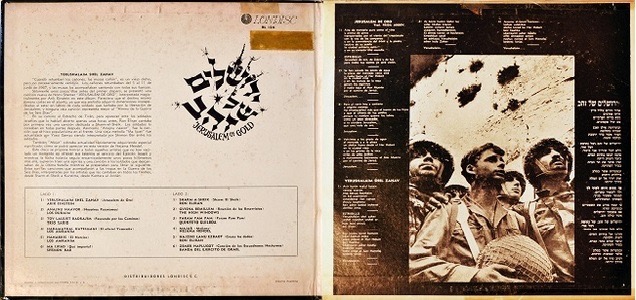

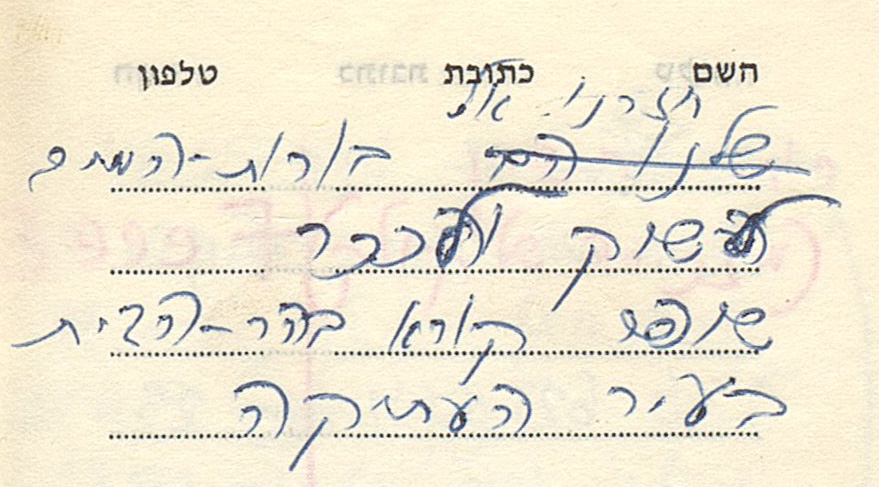

[caption id="attachment_11157" align="aligncenter" width="879"]

The new stanza as it appears in Shemer’s phonebook.[/caption]

The new stanza as it appears in Shemer’s phonebook.[/caption]In the euphoric days after victory, images of Israeli troops taking control of the Old City of Jerusalem and soldiers praying at the Wall appeared everywhere. People snatched up “Victory albums” and pictures of Moshe Dayan and Yitzhak Rabin. They travelled to the Old City. So giddy was the mood that MK Uri Avneri even proposed a bill to replace HaTikva, the Israeli national anthem, with Jerusalem of Gold. (The bill failed.)

But not everyone was swept up in the fervour. On the same day Shemer added the new stanza to her song, author Amos Oz critiqued Jerusalem of Gold in the Davar newspaper. “The market place was not empty, but full of Arabs,” Oz wrote. Twenty years later, on the eve of the anniversary of Jerusalem’s reunification, Shemer reaffirmed the song’s sentiments. “Jerusalem devoid of Jews was mournful and in ruins,” she said, “and the land of Israel without Jews was in desolation”.

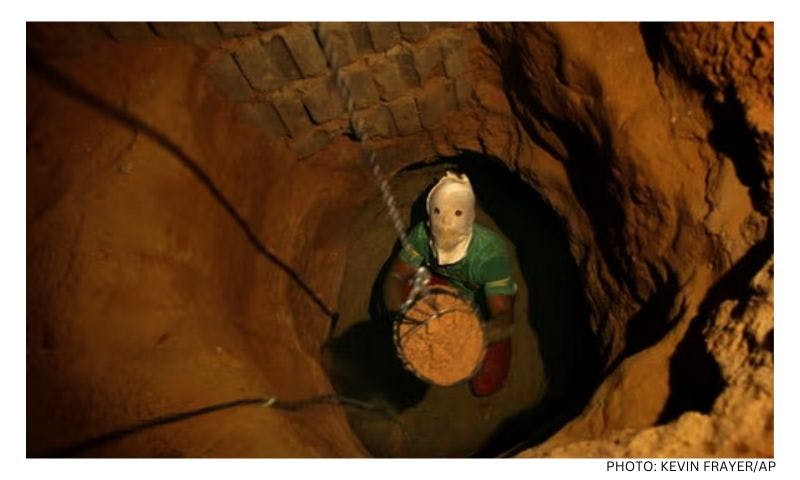

And then there were the soldiers themselves. The battles in Jerusalem were among the most intense in the war – killing 200 soldiers and wounding 1000. The paratroopers who liberated Jerusalem were proclaimed heroes. Yet, many of these soldiers suffered profound physical and mental injuries. They lost comrades-in- arms. Heady, euphoric Israel had no room for their grief.

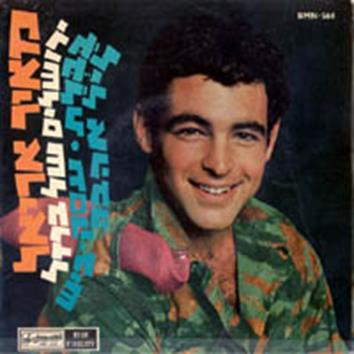

For one young paratrooper, Meir Ariel, the discord between the national mood and his personal torment was so jarring it was poetic. At about 4.30pm on the day of Jerusalem’s liberation, he watched dignitaries and officials rushing to Damascus Gate. He heard the excited chatter. “Everyone related to us as if we were gods, heroes, almost-saints,” he later explained.

On the bus journey out of Jerusalem, Ariel, surrounded by his fellow troops, began to reflect on the spectacle he had just witnessed. And he wrote a song, “just like that, for the guys. And the guys said they liked the song.”

The song’s name: Jerusalem of Iron.

And the same day Shemer published her new stanza, the day of Oz’s critique in Davar, Ariel’s paratrooper brigade gathered in the amphitheatre on Har HaTzofim (Mount Scopus) for a celebratory concert. After performances from various star entertainers, Ariel appeared on stage and sang his rejoinder to Jerusalem of Gold.

“I wanted to sing this song in front of a bonfire with my friends,” Ariel recalled of that night. “But there was no bonfire. There was no time for that. So when there was the first artistic evening in the amphitheater on Har HaTzofim, I jumped up onto the stage at the right moment… I just did it of my own initiative, out of some need to break the huge tension of those days. The guys know me as someone who writes rude songs for our own internal men’s gatherings. They figured that I was going to sing something like that again. They were probably surprised. ”

Ariel’s performance was recorded by a radio host. The next morning Jerusalem of Iron was broadcast on a domestic talk show, with Ariel described as a “paratrooper.” And that’s what he remained in the popular imagination: the singing paratrooper with a beautiful voice. The public was charmed: confronted with an anti-war anthem, they simply chose to hear what they wanted to hear— more patriotism, authentically rendered.

In the decades that followed Ariel went on to release nine albums, all considered Israeli classics. He died in 1999 at the age of 57. His posthumous fame has outstripped his popularity during his lifetime, reflecting perhaps an anxious longing for a “singing paratrooper” who can write, reflect and feel.

Ariel’s song, on the other hand, became a mere historical footnote, while Jerusalem of Gold soared to canonic status. Even he stopped singing it sometime in the 1970s. Israel’s patriotic hubris after 1967 set the country on a disastrous path to the Yom Kippur War, six years later. But while the heavy casualties of the Yom Kippur War forced an accounting on the true “price of war,” it did not awaken the public to the suffering of others. Those who had inhabited the Old City’s marketplaces and plazas before the Six day War, the “Other,” absent from Shemer’s song, are still invisible to most Israelis. The best example of this is the demonising, by the Israeli government and much of the public, of human rights organisations such as Breaking the Silence and B’tzelem that try to reveal the true price of the occupation, for both soldiers and Palestinians.

“Jerusalem of Gold is a beautiful song that represents the longing and yearning for Jerusalem,” Ariel told a television interviewer in 1997. “The Six-Day War killed the longing. The longing was like a beautiful and colourful butterfly and the war killed this butterfly and put it in the Butterfly museum - still colourful but dead.”

YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ar7l7Ja-3j0

Jerusalem of Iron

In your darkness, Jerusalem,

we found a loving heart,

when we came to widen your borders

and to overwhelm the enemy.

We became satiated of all his mortars,

then suddenly dawn broke,

it just arose, not yet even white,

and it was already red.

Jerusalem of iron,

of lead, of darkness,

haven't we set your wall free?

The strafed battalion broke forwards,

all of him in blood and smoke,

and a mother came, and another mother,

in the congregation of bereavement.

Biting his lips, not without toil,

the battalion continued fighting,

till, at the end, the flag flapped

above the house of bitterness.

Jerusalem of iron,

of lead, of darkness,

haven't we set your wall free?

The king's army dispersed,

the sniper his tower is silent,

now it’s possible to go to the Dead Sea

by way of Jericho.

Now it’s possible to go to Temple Mount

And to the Western Wall,

here, you are, in the twilight

almost all of you, gold.

Jerusalem of gold,

and lead, and dream

Will forever be Peace, between your walls.

This The Jewish Independent article may be republished with this acknowledgement: “Reprinted with permission from www.thejewishindependent.com.au”

Related: 50 years after the Six-Day War – writers’ divide still persists

Natan Alterman or Amos Oz? The Six-Day War and Israeli literature.

Comments

No comments on this article yet. Be the first to add your thoughts.