Published: 26 September 2018

Last updated: 4 March 2024

After fierce criticism from the right (another candidate for the presidency, the right-wing Francois Fillon, condemned what he called a “hatred of our history” and the “perpetual repentance that is unworthy of a candidate for the presidency of the republic”), Macron dropped the rhetoric for the duration of his campaign, and the whole first year of his presidency.

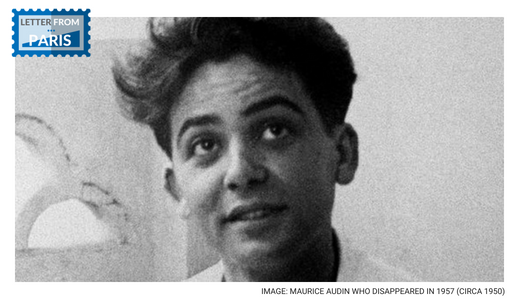

Until last week. In an unexpected statement released on 13 September, Macron acknowledged the responsibility of the French state in the torture and death of Maurice Audin in 1957.

Though he stopped short of a full mea culpa for the French state, limiting the acknowledgement of culpability to the specific case of Audin, his words announced yet another sea change in the complex dynamic of remembering and forgetting in French historical memory.

The letter that was signed by Macron and delivered to Audin’s widow Josette – who has been unrelenting in her pursuit of the truth of what happened to her husband – was the first time that the French state has acknowledged the use of torture during the Algerian war by the French army.

Audin was married with three young children, a brilliant young mathematician, an assistant professor at the University of Algiers and a committed member of the Algerian communist party, militantly in favour of Algerian independence.

He was arrested at his home on June 11, 1957 and last seen alive by a fellow communist the day after his arrest. His family had no official comment about his death from the army until last week.

When the news broke, it was hard to avoid recollecting the speech made by newly minted French president Jacques Chirac on 16 July 1995. Barely two months into office, Chirac became the first ever official to acknowledge French responsibility for the arrest of 13,000 Jews in Paris in 1942 in the notorious round up known as the “rafle of the Vel d’Hiv”.

They were imprisoned for several days in a velodrome in central Paris, from which a handful managed to escape; the rest were sent to the Drancy concentration camp north of the city and then to Auschwitz. Almost none survived.

Chirac’s declaration that, “These dark hours have forever soiled our history, and are an insult to our past and our traditions…. Fifty-three years ago, on July 16, 1942, 450 French police agents and gendarmes, acting under the authority of their leaders, responded to the Nazis’ demands” sent shockwaves through the country, which had sustained a carefully constructed myth of widespread resistance for half a century.

His words were an extraordinary rebuttal to his predecessor, socialist president Francois Mitterrand, who had always insisted that the blame lay solely with the Nazis and the Vichy collaborationist government.

Mitterand’s position reinforced the view of Vichy as a kind of parenthesis in French history: “I will not apologise in the name of France. The Republic had nothing to do with this. I do not believe France is responsible.”

[gallery columns="1" size="large" ids="23092"]

Mitterrand’s own wartime past was murky – he was always open about his activities in the Resistance, rather less so about the fact that before he joined the resistance he was a penpusher for Vichy. He remained unapologetic about his friendships and political relationships with several Vichy collaborators after the war, one of whom, René Bousquet, had been secretary general of the police under the Vichy regime – and principal organiser of the Vel d’Hiv roundup.

What has become known as the “Audin Affair” has other historical resonances too. People talk of the Dreyfus “echo”, referring to the Dreyfus Affair that divided France in the dying days of the 19th century. Dreyfus was a senior office in the French army, who was convicted on trumped up charges of spying and sent to Devil’s Island, a notorious French prison off the coast of French Guiana.

The case was a cover-up – the army knew Dreyfus was not guilty but it took eleven years for him to be officially exonerated. His conviction was clearly motivated by anti-Semitism lodged in the heart of the army and the French establishment, and the affair divided the country into pro and anti “Dreyfusards”, just as half a century later France would be split on the question of Algerian independence.

Audin had his Zola too: the historian Pierre Vidal-Naquet. Vidal-Naquet was one of the few members of his immediate family to survive the Holocaust and went on to become one of the most respected French historians of the latter part of the 20th century.

In 1958 he published his own “J’accuse” (the first words of Zola’s letter to the newspaper L’Aurore in which he accused the army of anti-Semitism in its pursuit of Dreyfus), a book called L’Affaire Audin.

In it he claimed that Audin had been tortured and then accidentally killed by an army officer, which had then covered up the truth in its relentless and vicious suppression of all those who supported the independence movement.

More than 50 years after Algeria won its independence and shook off the yoke of the colonial oppressor, France is belatedly and painfully conducting a reckoning with its past. Perhaps now the deep wounds left on both sides by this bloody war can begin to heal.

Main photo: Maurice Audin who disappeared in 1957 (circa 1950)