Published: 19 October 2021

Last updated: 4 March 2024

From their bohemian roots in New York, poet Magdalena Ball and her composer uncle Ricky Gordon have become artistic mentors to each other

Magdalena Ball, 57, is a novelist and poet who moved to Australia from the US more than 30 years ago, and now lives in West Lake Macquarie, NSW. She has recently written a book of poetry about her maternal great-grandmother Rebecca.

Her uncle Ricky Ian Gordon, 64, is an American composer based in New York. His recent operas include The Garden of the Finzi-Continis, produced by the National Yiddish Theatre Folksbeine.

Magdalena (Maggie)

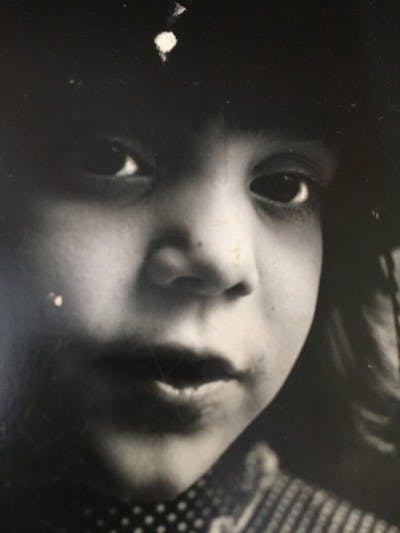

I was born in New York City in 1964. My mother was only 17 when she had me. There were four children in her family, she was the second and Ricky was the baby, so he was only eight years older than me.

Because my mother was so young, my grandmother Eve, Ricky's mother, spent a lot of time looking after me. We were very close.

My grandparents’ house was always filled with music; mostly Ricky playing piano and my grandmother singing. She sang to me a lot in Yiddish. Before she married she had sung in the Borscht Belt in The Catskills and later in her forties she started doing musical theatre.

My sense of what it means to be Jewish is kind of bundled up in my grandparents and that whole sense of the foods that my grandmother would make, particularly lokshen noodle pudding and blintzes. She was always cooking, always feeding people. There were always people coming to the house. There was always coffee on the ‘perc’.

Ricky's friends always came round and my grandmother was incredibly accepting. His friends were always really funny, interesting arty people, and they were always really warm and generous to me. They didn't treat me like some kid and Ricky always treated me with a lot of respect too.

I remember once, I’d been writing some really bad poetry, Sturm und Drang, full of intense emotions and kind of like Sylvia Plath, but as a 12-year-old. Instead of saying, “maybe you should do something else,” Ricky said to me, “I love your work and why don't you read these books?”

He bought me a pack of about maybe four or five poetry books, all of which I still have. And they included Sylvia Plath’s Ariel, Anne Sexton’s Live or Die, Rimbaud’s The Drunken Boat, and Bertolt Brecht’s Manual of Piety.

I was maybe too young for that kind of material, but he treated me with the kind of respect that someone of that age really craves. He said to me, “you know, you have talent and you have a future in this”. And that just stayed with me. I don't know whether I'd still be writing poetry if he hadn't given me those books and that encouragement.

Ricky’s a lot of fun to be around. He's always full of stories. He's very funny. He's charming. He's talented. He's got a prodigious memory. So whenever I see him, he'll quote some poem to me, but in full, from start to finish. He'll say, “Oh, Mag, you’ve got to hear this, you know, just listen to this poem.”

The research that I've been doing on Rebecca, my great-grandmother has really forced me to start thinking more about notions of inheritance and trauma and what it means to be connected to a people that have been oppressed in such a way. There's also many wonderful, beautiful traditions.

But I do feel, as I start to find more about my grandmother, Ricky's mother, or read about the things that he went through,that there is this kind of genetic thread that links all of us. What have we inherited from one another and how do we heal from that as well?

So it’s more than just “Ricky's Jewish and I'm Jewish”. It's about tracing what it means to be part of this tribe and to reach back into what our people went through, and see a way through that and say, how do I practice tikkun olam? How do I make this world better?

RICKY

Maggie and I - I would say we're more like brother and sister than uncle and niece, except she lives so far away. But we always have this very close connection and we really got much closer this year because Maggie is brilliant. She's shockingly brilliant, and she took the: “I am going to read and write poetry gene” to the nth degree. At Oxford! So I've always been really proud of her.

And this year I really needed her. I started writing this [memoir] and I needed Maggie. I needed a reader.. She would read things and she always knew what to say to keep me going, which direction to go in.

There is also this thing in our family that anyone has a hard time of leaving the family behind. It seems like we all have this need to include the family in our work. Maggie and I right now are like the excavators, digging the Gordons out from the ashes in Europe.

My mother grew up in Harlem and my dad grew up in the Bronx but their parents were all escapees from antisemitism pre-World War Two, from the pogroms. And as the only son, I, of course, was the one who was given a Jewish education. That was just tradition.

So I had to go to Sunday school and to Hebrew school and I was bar mitzvah-ed. But the interesting thing is that it didn't spark anything in me. It was not a spiritual education. I didn't really know what it meant to be a Jew.

And it could be that because [at home] there was no structure of being a Jew, the structure of the religion that scaffolds to hang your life on, that I shot out like an unsupervised, feral animal and I used drugs and indiscriminate sex and drank.

And the only anchor, the only thing that pulled me back every time from the precipice, was art. I had a gift. The desire to make something beautiful was very strong in me.

When I was 33, I finally I got sober. No drugs, no alcohol. And then things really started happening. And this is where the Jewish part started coming into my music in a really interesting way. When I wrote Morning Star, the opera ends with the Kaddish for all the women in the shirt factory who have died.

And when I was writing it, I was very aware that this was the Kaddish for my father. This would go into the world and it would always be there. I felt like that's the way I can do Kaddish for my father.

At the time, my lover, Jeffrey, had just died of AIDS and we played the recording of my friend, playwright Tony Kushner, saying the Kaddish over Jeffrey's grave and it's like my Jewishness started to come out in a way that felt beautiful and manageable. I started understanding more what it meant for me to be a Jew.

Being Jewish makes me feel more whole, like I'm not running away from anything and I'm not denying anything. But I'm also not pretending any kind of holiness that I don't feel. It will always be mine and I don't have to do it in the way other people do it. It's already in me.

Maggie's become such a mentor for me. She listens to everything I write. We're close and we're artists in collusion. Maggie and I are like Jewish fugitives walking in the same direction. When she was a girl, I really feel like I whispered art into Maggie.