Published: 12 May 2018

Last updated: 4 March 2024

The Russian-speaking population has a very different settlement experience and adaptation from the other two.

In the 1970s a mass exodus started, culminating in the 1990s with about two million Jews who emigrated from the Former Soviet Union (FSU). The main destination of Russian-speaking Jews was Israel, but large numbers immigrated to the USA and Germany, with smaller numbers to Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

My research of unpublished and published Australian government documents and databases shows that between 12,000 and 13,000 Jews from the FSU immigrated to Australia during two migration waves in the 1970s and 1990s. They arrived mainly under the humanitarian migration stream made possible by specially devised Australian visas for Minorities from the USSR.

The Soviet regime discriminated against Jews both culturally and socio-economically. Religion in the Soviet Union was mostly banned, and atheism was propagated in its stead. One result of this was that Jews could not openly provide their children a Jewish religious education, after hundreds of cheders and yeshivas (Jewish schools), and synagogues were closed by the Soviet regime.

After WWII, the Soviet regime gradually restricted public Jewish culture and Soviet Jews became increasingly Russified; especially the new generation born during that period. Their Jewish identity constituted mainly of their Jewish ethnicity and was separated from religion. Jews in the FSU were often regarded, including by themselves, as Jewish by nationality—which was the nationality imprinted in their passports.

The Soviet Union was an authoritarian and state-controlled economy which meant that the regime could discriminate against minority populations. This indeed was the case for Soviet Jews who were increasingly discriminated against socio-economically from the late 1960s. Quotas were imposed on the number of Soviet Jews who could attend universities and fewer Jews were promoted to prominent positions.

It was from this situation that Jews from the FSU immigrated to Australia. Their Russian-Jewish culture was "thin", at the same time their Jewish nationality served as a catalyst for socio-economic discrimination against them. With this identity, Russian-speaking Jews needed to adapt to vibrant Jewish communities in Australia.

It can be expected that - as humanitarian immigrants - Russian-speaking Jews would experience difficulties when settling in Australia. As indicated by the Gen17 survey, their main difficulty was with the English language; 77% compared to 41% of Israelis.

Language proficiency is often viewed as a decisive factor for socio-economic and cultural adaptation. The poor level of English language proficiency was reflected in other difficulties Russian-speaking Jews experienced when arriving in Australia. They also indicated difficulties finding suitable employment (59%); inadequate income (59%); and inability to afford adequate housing (49%).

Language barrier and cultural differences can often result in discrimination; 16% of Russian-speaking Jews indicated discrimination at work and 28% when mixing with Australians. Israelis indicated slightly lower levels of discrimination; 12% at work and 24% when mixing with Australians.

Discrimination was not confined to interaction with non-Jews. Russian-speaking Jews and Israelis indicated a level of discrimination (26%) from Jewish people or the Jewish community similar to that of when they mixed with Australians.

Discrimination was not confined to interaction with non-Jews. Russian-speaking Jews and Israelis indicated a level of discrimination (26%) from Jewish people or the Jewish community similar to that of when they mixed with Australians. Higher proportions further indicated difficulties meeting and making friends in the Jewish community; Russian-speaking Jews 44% and Israelis 39%.

With a "thin" Russian-Jewish culture mainly experienced as a nationality, it can be expected that the Jewish identity of Russian-speakers was mostly in reaction to anti-Semitism and their sense of being a historically persecuted minority.

This was indeed the case as Russian-speaking Jews mainly indicated that remembering the Holocaust (78%) and combatting anti-Semitism (70%) were very important for their sense of Jewish identity.

To a lesser degree, Russian-speakers also had a "positive" Jewish identity and indicated that upholding strong moral and ethical behaviour (64%) and feeling part of the Jewish people worldwide (57%) were very important for their sense of Jewish identity.

Upholding strong moral and ethical behaviour can be viewed as the “positive” expression of remembering and fighting immoral behaviour (Holocaust and anti-Semitism). Whereas feeling part of the Jewish people worldwide is often the expression of a "positive" ethnic identity.

In contrast, a much higher proportion of South Africans (78%) and Israelis (69%) indicated sharing Jewish festivals with their family as very important for their Jewish identity compared to Russian-speakers (45%).

Having experienced difficulties when first settling, can we expect Russian-speaking Jews by now to feel a sense of belonging in Australia? The answer is yes, with a similar proportion of Russian-speaking Jews (82%) who felt a strong sense of belonging in Australia compared to South Africans, while Israelis had a much lower proportion (63%).

In conclusion, are Russian-speaking Jews much more satisfied with their life in Australia compared to their home countries? The answer is an astounding yes, especially when compared to Israelis (36%) and South Africans (55%): 70% of Russian-speaking Jews were much more satisfied in Australia.

RELATED ARTICLES

Tough love – What Gen17 teaches us about Israelis living in Australia

Gen17 Australia: rising intermarriage, huge school fees, endemic poverty

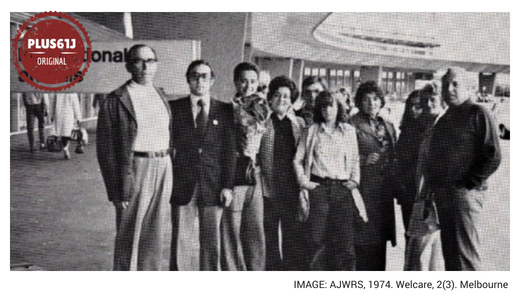

Photo: Recent arrivals from the Soviet Union met by relatives in 1974 at Tullamarine Airport (Source: AJWRS, 1974. Welcare, 2(3). Melbourne)