Published: 19 August 2020

Last updated: 5 March 2024

I GREW UP IN EAST BRUNSWICK in post-war Melbourne and came from a family of Bundists, so it was only a matter of time before my older cousin Charles took me to SKIF. An acronym for Sotsialistishe Kinder Farband (Socialist Children’s Union), SKIF was formed in Poland in 1927 by members of the Jewish Labour Bund so their children could learn about history and politics, absorb Yiddish culture and, above all, have fun.

In 1950, following the mass migration of Eastern European Jews to Australia, two members of the Bund - Pinkhas (Pinie) Ringelblum and Symkhe Burstin - founded Melbourne SKIF. In 1962, I was eight or nine, and Charles, five years older and my childhood hero, was already well known in the Bundist movement.

Charles, universally known as “Sluggo”, lived with his sister Miriam and their parents in a little, single-story terrace house in Canning Street, North Carlton, right in the middle of a neighbourhood composed almost entirely of Eastern European Jewish immigrants plus a smattering of Italian and Irish-Australian working-class families.

Every Sunday, our whole family would gather at my auntie’s house for lunch after we finished at Peretz School, where we learnt Yiddish language and culture. It was a great way for the parents to embed Jewish secular culture into us. But for many of us, the best thing about Peretz School was it meant that it was only a few hours before we’d be going to SKIF.

[gallery columns="1" size="full" ids="37537"]

Around 1.30pm, two of Sluggo’s friends, the Zable brothers, who lived a few blocks down the same street, would come to the house, and the four of us would set off on the short walk to Carlton SKIF. Arnold Zable later became a SKIF leader, a renowned human rights activist, and an award-winning author. Harry, his younger brother, became an accomplished artist.

I was in seventh heaven: Going to SKIF - with the big kids!

We would soon arrive at the old Kadimah (“progress” in Hebrew) building in Lygon Street, home of the Jewish cultural organisation. The building is still standing, but after the Kadimah moved out to the southern suburbs in the late 1960s to be closer to the new epicentre of the Jewish community, it became a Sicilian function centre.

Back in 1962, Carlton SKIF held its meetings and activities there. Sluggo and his friends dropped me off with some children my own age, while they went off with the older groups. I still remember the ambience of that building – brown, lots of brown, brown chairs and brown tables and brown cupboards and brown bookshelves and brown decorations – brown, brown, brown. And a musty smell, sort of like old books and newspapers – which makes sense given that it was a library filled with old books and newspapers.

[gallery columns="1" size="large" ids="37544"]

I have no recollection of what we did there. I don’t even remember who the other SKIFists were. I do remember the first two "helfers" I had. A helfer (helper), who tended to be 18-20 years old, was a combination of leader, mentor, teacher, coach, and babysitter – the closest thing to it would be a camp counsellor. That first day, my helfer was Pearl Zucker, who stopped after a few weeks (though I’ve since known her my whole life). My second helfer was the late Fay Mokotow, one of the most significant and influential people of my early life.

I loved Fay and over the next 20 years, got to know her in many different roles – as a professional actor at the La Mama and Pram Factory experimental theatre groups, as a brilliant director of Itzik Manger’s Megillah and other Yiddish plays I acted in at the Melbourne Yiddish Youth Troop, and as a very accurate and fast typist who typed my final year philosophy thesis on Ludwig Wittgenstein.

I fondly remember driving to her little terrace house in Carlton every week during the final semester of my third year of university. My enduring image of Fay is of her standing at a SKIF camp in one of those old royal blue SKIF shirts with a flaming red SKIF bandana around her neck, clapping her hands, and singing Tumbala-laika.

[gallery columns="1" size="large" ids="37541"]

SKIF camp

When I was 10 years old, the real fun started. We went to SKIF Camp in Dromana – a small seaside holiday town a few hours from Melbourne. I already had a history with Dromana because my parents used to take us to Kelly’s Guest House during the summer holidays. It was an old-style hotel/B’n’B run by an Irish-Australian family, patronised predominantly by Jewish immigrants. Kelly’s was easy to get to for us and many other new Australian, car-less families because it was right next door to SKIF’s campsite in Dromana, so our whole family (along with a few others) would hitch a ride on the (very packed) camp bus.

In those days, no-one worried too much about overcrowding, or many other health and safety issues. I remember standing for part of the ride, and everybody singing Yiddish songs – Zingendik, Tumbala-laika, Mir Kumen On – and yelling out the SKIF motto Khavershaft (friendship) whenever one of the helfer yelled out “SKIF!”

Khavershaft was SKIF vernacular for sharing, for camaraderie, for amity; a way to speak to children about the best aspects of democratic socialism. I got introduced to it on that first bus ride, and it became part of my vocabulary at that tender age.

There were other rituals of camp that stayed with me. On the day that we would depart for camp, Khaver Hershl Mokotow, the president of SKIF Freynt (SKIF Friends) would do a slow roll-call standing outside the bus, and read out each camper’s name before he or she was allowed on the bus. For us, this always signalled the beginning of camp.

[gallery columns="1" size="full" ids="37540"]

On the last day of camp, David and Maurice Burstin, who had been among the first Australian SKIFists in the early 1950s, would always come along and help us pack up the tents and other equipment. Seeing David drive up on that last Sunday would signal the beginning of the end of that year’s camp.

At my first camp, we were divided into groups by age. These groups were called kraizn (circles) and were all given significant names honouring heroes of the Bund movement.

I was placed in the second youngest kraiz and we were called Yunge Boyer (Young Builders), and Sluggo was our helfer, his first year in that role.

After lunch on the first day we would pick a nickname which would be ours for the duration of the camp. I picked Spud, because I had known someone who lived on Canning Street with that name and I thought it was quite cool. It stuck, and for my whole SKIF career I was known as Spud. Some people still call me that.

[gallery columns="1" size="full" ids="37536"]

After that first camp, there was no stopping me. I went to every possible camp – both summer and winter camps. I went to junior camps at Dromana, till I was of senior age (around 13), and then went to senior camps at various seaside and country towns in Victoria.

I was involved in writing numerous songs, penning and acting in Yiddish plays, performing skits in English and Yiddish, and playing in many skoitn shpiln (scout games) which were simulations of historical or fictional rebellions, battles, or uprisings.

I worked with others pitching and folding tents, cleaning bathrooms and toilets, digging ditches, setting tables, and washing dishes. I was a member of many a camp council where I was involved with self-government.

We participated in nocturnal raids where a bunch of us would get up in the middle of the night, sneak into other groups’ tents, and paint the faces of fellow campers with toothpaste while they slept. We went on 20-mile hikes, we created giant campfires where we would gather around to sing Yiddish working-class songs, English folk songs, and funny made-up ditties, after eating typical campfire fare like sausages or lamb chops between pieces of cardboard-like white bread.

[gallery columns="1" size="full" ids="37542"]

We had several themed days – both humorous and serious. Who could forget the annual Tog fun Nakht (Day of Night), where we would be woken at around midnight, rousted from our tents for “morning exercises”, then ushered to the breakfast tables to begin a whole “normal” day that took place at night?

There was also a Tog fun Freyd (Day of Joy), where the helfer had us do all sorts of quirky activities – we had meat and veg for breakfast and cereal for dinner, we pulled the flag down in the morning and raised it at night, and pretty much anything that seemed to be the opposite of what we would expect.

One of the most poignant days was the Tog fun Khurbn (Holocaust Day), a whole day of learning about and commemoration of the Holocaust. We were a highly educated group of children and teenagers. But it was a double-edged sword. This experience left me aware of man’s inhumanity to his fellow man (and woman), alert to inequality, and quite an activist at a young age. At the same time, it led to many a sleepless night and had me lamenting the future of humanity at a much younger age than most of my school pals.

However, these challenges also gave us a platform for speaking up and a vehicle for making a difference. We were taught that we not only had a right, but also an obligation, a duty to question the way things were. We didn’t only weep for the downtrodden; we spoke about possibility and action. Discussions about how the world could be and conversations for what we should do about it.

As well as the old activists from our community, we would get young Aboriginal activists to speak to us about their experiences, and Labor members of parliament and Fabian Society intellectuals would talk to us about what we could do to change the world.

In 1970, we even took a 12-hour bus ride to Canberra to join a mass protest with other Jewish youth groups beseeching the Soviet Union to allow its Jewish citizens to emigrate.

[gallery columns="1" size="large" ids="37543"]

Many of us participated in the progressive movements of our time, such as the Vietnam moratorium marches of the early 1970s, the protests against the flooding of Lake Pedder and the Franklin Dam in the 1970s, the push for Aboriginal Land Rights in the 1990s, and more recently the refugee and asylum-seeker action groups, the fight for same-sex marriage, the climate change rallies and the anti-racism demonstrations.

I made lifelong friendships at SKIF. At 67 years of age, I feel the people I met on my first few camps are still among my closest friends. There’s a large body of shared memories and experiences and a depth to the friendships, a common heritage, a common set of beliefs. We tend to look at the world through the same filter. That’s not to say we never disagree on issues, but we do seem to come to our views from the same place. There is something comforting and familiar whenever we’re together.

[gallery columns="1" size="full" ids="37548"]

The end of an era

We were the last of an old generation of SKIFists, one whose parents had lived through the Holocaust, and was the product of the 1960s counterculture. Our generation caused and saw a lot of change in the world around us, which was reflected in a transformation at SKIF itself during the late 60s and early 70s.

Carlton SKIF closed soon after I started; almost every Jewish family had moved either to the southern or the eastern suburbs and we would make our way to Waks House (named for Yankev [Jacob] Waks, a Bund leader in Australia in the 1940s and 50s) in St Kilda by tram or car.

Within a few years, most people didn’t even remember that SKIF used to meet at the old Kadimah, let alone what it looked and smelt like inside. There is a new SKIF headquarters now in Caulfield, a south-eastern suburb with a large Jewish population, and it too is called Waks House.

I was the camp commander of the last SKIF camp at our own campsite in Dromana in 1971-72. We tried to revolutionise the way junior camps were run. We gave the campers lots of freedom and not much discipline, but truth be told, it was a bit of a disaster which seemed to leave a bad taste in the mouths of the traditionalists. But that’s not the reason we stopped having camps there. No, it was deemed to be time to move on. Pretty soon, tents were phased out as well, and campsites with little huts and cabins were found all around Victoria.

[gallery columns="1" size="large" ids="37546"]

Another sign of change was our new uniforms. In the early days we used to wear deep royal blue military-style shirts with button-down pockets and epaulettes, with flaming bright red kerchiefs or bandanas that were tied loosely around our necks. In the 1970s, in our infinite wisdom, we thought that they looked too aggressive and militaristic and we introduced SKIF T-shirts – deep royal blue crew-neck T-shirts emblazoned on the front with the SKIF emblem, a flaming red falcon (a bird which flies against the wind), and SKIF written in English and in Yiddish around it. They did look very cool when we first got them.

Other links to the older generations have started to fade. Pinie Ringelblum and Symkhe Burstin still came to our camps in the late 1960s – to lead activities, to help set up, and occasionally, to read us the riot act. Who could ever forget Khaver Pinie instructing us on how to preserve the tank water by turning on the tap oh so slightly … rather than letting it all flow out “bul”.

And how vividly I remember Khaver Symkhe teaching us funny little Yiddish songs – Mein hut es hot drei ekn (My hat has three edges) and Tsu kent irh shoyn dos naye lid fun dem barimtn kupershmidt (Do you know the new song from the famous coppersmith?) to the tune of The Red Flag.

These rituals and customs have disappeared with the passing of time. At first, I lamented their passing, but I eventually accepted that the loss was superficial – the movement’s soul and the camp’s intent hadn’t really changed. Khavershaft remained as important as it had been in our time.

[gallery columns="1" size="large" ids="37547"]

Epilogue

When we returned from camp and went back to school, there was a feeling among most of us that we were special, somehow different. We were SKIFists. In all honesty, this feeling was quite elitist. But it was almost universal, and I suspect that kids today still have that same after-camp glow and that longing to be back at camp, in their SKIF attire, banging out Olympiade songs, singing the SKIF anthem Git Di Hent Zikh Shvester Brider (“Let’s hold hands, brothers and sisters”) and looking forward to the campfire.

Sure, they probably do it with their iPhones and their iPads, complaining that the wi-fi isn’t working fast enough. But I saw my daughters go through SKIF with the children of my SKIF friends, and my eight-year-old grandson has now started SKIF the same way – with the grandchildren of my SKIF friends.

In these strange times, he has been doing SKIF every week via Zoom on his laptop, but he still sings those songs, still plays the same games, still rhythmically chants, “Kha—ver—shaft” whenever one of the helfer yells out “SKIF!”, and he still spends the whole week looking forward to Sunday, to his two hours of SKIF.

And mention camp to him? He is as excited as I ever was; he cannot wait!

A few months ago, when his third-grade teacher tasked him with doing a research assignment on a topic of his choice, he picked Marek Edelman, the young Bundist leader who was one of the leaders of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. He did some Wikipedia research and wrote a three-page paper.

I know that the brown chairs and tables and bookshelves of the North Carlton Kadimah are as far away from him and his friends as those old books and newspapers are from their smart phones, but in their own way, I can still see them laughing, dancing, and singing, and above all, shouting “Zol Lebn Der SKIF!” (Long live SKIF)!

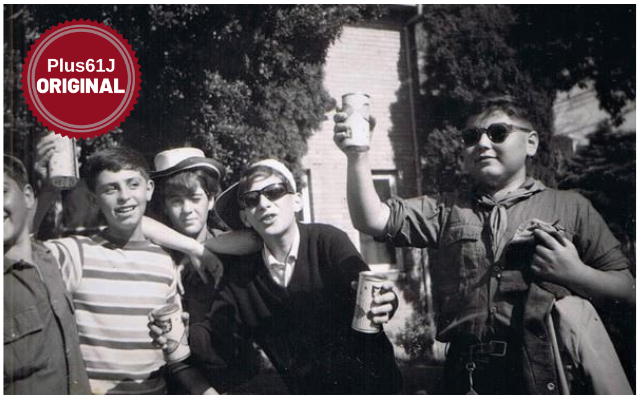

Main photo: Moshe Goldberg in black sunglasses and black jumper, second from the right, with friends at the old Waks House in St Kilda, about to board the bus for his third camp