Published: 25 March 2022

Last updated: 4 March 2024

MICHAEL GAWENDA: The Finks were part of that unique group of Jews who helped transform Australia’s postwar Jewish population into a vibrant, flourishing community

IN NOVEMBER 1949, the passenger ship the Continental arrived at the docks in Port Melbourne. Among the 200 or so passengers on board, most of them Jews from the displaced persons (DP) camps in Austria and Germany, was my family. My mother, my father, my three older sisters and me. I was born in a DP camp in Linz, Austria, and lived there with my family for almost the first three years of my life.

Given my age when I was carried off the Continental by my oldest sister, who by then was married and pregnant with her first child, I have no memory of the moment I first touched the ground in Australia. Nor do I recall who was there to greet these Jews, most of them refugees and Holocaust survivors.

But my father and my sisters told me when I was old enough to listen, that some lovely Jewish people had been there on the dock to greet us. They did not, as far as I can recall, say that Mina or Leo Fink were among them.

But having now read Margaret Taft’s book, Leo and Mina Fink: For the Greater Good, having read about the way Leo and Mina had been there for virtually every ship arrival carrying Jewish refugees—how they had worked so tirelessly to get the Australian government to accept these Holocaust survivors, how they had been key players in establishing the refugee and welfare organisations that helped bring thousands of these broken traumatised people to Australia, I was pretty sure that either Leo or Mina Fink, or both of them, were there on the dock to greet us.

Theirs is a remarkable and inspiring story and Margaret has told it with sensitivity, warmth and the benefit of her training as an historian.

These two Bialystokers arrived in Melbourne in June 1928, still in their twenties, full of a zest for life, for success, for a rich and deep Jewish life and above all, with a commitment to Jewish continuity and growth in this new far away country.

For the next half a century and more - Leo died in 1972 and Mina in 1990 - the Finks were part of that unique group of Jews, some who arrived in Australia in the 1920s and 30s and some in the 40s and 50s, who helped transform the Australian Jewish community, small in numbers, into one of the most vibrant, most culturally rich, and economically successful Jewish community in the world.

I am a beneficiary of their dedication, the relentless lobbying of governments, the endless committee meetings of the welfare and refugee rescue organisations they helped establish.

It was a sort of miracle that this group of Jewish leaders, Mina and Leo prominent among them, was able to help settle thousands of traumatised and often destitute Jewish survivors of the greatest tragedy in Jewish history. And not just settle them but help them in every conceivable way make new lives for themselves and their children in this faraway place that few of them had ever heard of before their arrival in Australia.

I am a beneficiary of their dedication, the relentless lobbying of governments, the endless committee meetings of the welfare and refugee rescue and settlement organisations that they helped establish and run. We are all beneficiaries of the thousands of exit visas they managed to scrounge from an immigration department, public servants who were not all that enamoured of the idea of thousands of strange looking and sounding people, Jews, strangers in other words, coming to Australia.

At this terrible time, when a tyrant is laying waste to a country and a people that he says do not exist, and with millions of Ukrainian refugees forced into exile, the question of how the world handled and treated the Jewish refugees and Holocaust survivors after the war is pertinent. What can we learn from their treatment?

In my view, the treatment was appalling, with restrictions everywhere in the West on the numbers of Jewish refugees, specifically Jews, that would be given refuge. I think Australia behaved no better or worse than the US or Britain for that matter. Arthur Calwell, the architect of Australia’s post was mass immigration program is a complicated and, in some ways, controversial figure when it comes to Australia’s treatment of the Jewish refugees.

I think Margaret Taft comes down on the side of those who believe that Calwell, even while he introduced a quota of 25 per cent of Jewish refugees on board any of the boats bringing migrants and refugees to Australia, turned a blind eye to the fact that people like Leo Fink and others consistently subverted the quota system.

Is she right? I don’t know. My feeling is that she is too kind to Calwell, even though recent research by the historian Sheila Fitzpatrick suggests that more Jewish refugees, significantly more, were admitted to Australia than the official figures record.

There is no doubting though that none of the Western countries have a record to be proud of when it comes to saving Jews before the war or settling the shattered remnants after it.

Nor is the postwar history of our accepting refugees and asylum seekers anything to be proud of; not us and not most of Europe and not the United States.

Nor does Israel have a record to be proud of when it comes to asylum seekers and refugees who are not Jewish. Israel, the Jewish state, is turning away Ukrainian refugees who are not Jewish. I wonder whether that’s what it means to be a Jewish State? A state of refuge for Jews only.

Let me go back to the Finks. My connection might have started with my family’s arrival aboard the Continental in November 1949 but it certainly did not end there. Indeed, it stretched over decades. Not long after our arrival in Australia, my father, who had been a master weaver in Lodz before the war and had run a small weaving factory from one of the apartments in the building where we lived, went to work first at one of the Fink factories in Northcote.

Later, he worked for almost two decades at United Carpet Mills in Preston where I often went with him during the school holidays and was given the job of cleaning up the bits of wool around the rows of large weaving machines which my father, when he became a leading hand - he called it lead fachman - helped maintain. He worked there until shortly before his death in 1971 and I remember going to the factory to pick up his last pay packet.

My memory is that he loved the job and was proud of his skill and expertise. I do not recall ever seeing the big bosses, Leo Fink or any of his brothers, but I remember that my father often said it was a good place to work for a refugee Jew like him.

Perhaps he did meet the big boss elsewhere but I do not know this to be true and there is no one I can now ask about it.

On Sundays, my father put on his Sunday suit and went first to the Sholem Aleichem Sunday school in Elsternwick where he sat in a small shed and handed out blayers un heftn to the children.

The life journeys of Leo and Mina Fink are astounding, from their childhoods in their beloved Bialystock to Melbourne where Leo and his brothers built factories that employed hundreds of people.

When school finished, he went home for his regular Sunday lunch of lokshen mit yorch followed by boiled chicken and then invariably, he headed off to the Kadimah in Lygon Street Carlton where he would attend one of the lectures by the great Yiddish teacher and writer Joseph Gilligich or by one of the international guest speakers who lectured on some aspect of Yiddish culture and literature, and then he would spend an hour or two in the library talking to some of his fellow Yiddishists.

When I was old enough, I came with him to attend my weekly meeting of SKIF, the Bund’s youth organisation. One of my helfers was the late David Burstin, son of Sender Burstin who arrived in Australia at around the same time as the Finks.

From the late 1920s onwards, they became close friends and fellow leaders who worked together for many years in Jewish welfare and on the Kadimah committee, where Leo Fink the Zionist and Sender Burstin the Bundist, shared a love for Yiddish and Yiddish culture and helped make the Kadimah a centre of Jewish life in Melbourne.

Perhaps Leo Fink was there at the Kadimah some of those Sunday afternoons and perhaps he even spoke to my father, who was as well read in Yiddish as anyone I have ever met. The idea is lovely. The industrial worker and the factory boss engaged in deep discussion about Sholem Aleichem’s use of Talmud references or the meaning of Peretz’s short story Bonshe Shvieg. Did it ever happen? I hope so.

Looking back, such a time will never come again. They were a group of leaders who dedicated every spare minute they had - when they were not working 12-hour days building businesses - to work for Jewish organisations, volunteers, who gave away their evenings to committee meetings of organisations that transformed the Melbourne Jewish community from a largely Anglo community of people of the Hebraic faith into some sort of rebirth of the sort of communities of Eastern Europe that had been destroyed in the Holocaust.

Margaret’s book tells the story of two remarkable people, but it is also the story of these group of leaders who helped in the healing of the remnants who survived the Holocaust and who arrived often without hope in this strange and vast continent.

The life journeys of Leo and Mina Fink are astounding, from their childhoods in their beloved Bialystock, the place that spiritually, Mina in particular, never left, to Melbourne where Leo and his brothers built weaving factories that employed hundreds of people and where the Finks quickly immersed themselves in Jewish communal life. They became wealthy and they travelled overseas regularly and they mixed in Melbourne society circles and both loved the theatre and opera and their beach house in Frankston.

But at the centre of their lives was their commitment to the Jews, to Israel - both were passionate Zionists - and above all to Jewish survival and Jewish recovery from the near-genocide of Europe’s Jews. Margaret’s book details their journeys through Jewish organisations and through the ever-changing Jewish communities around the world, most particularly in Israel and Australia.

Their journey took them through the terrible war years (Leo was a reservist) when they worked desperately to do whatever could be done, and more, to rescue as many Jews as they could, even as the Nazis strove to exterminate the Jews of Europe.

These were desperate time and there were desperate times postwar when thousands and thousands of Jews, their homes destroyed, their families murdered, desperate to get as far away from the mass graves of Europe, languished in DP camps in Austria and Germany.

Leo and his fellow Jewish leaders succeeded to such an extent that Australia became home to the largest number per capita of Holocaust survivors, after Israel, in the world.

Leo was a magnificent networker and a great lobbyist. He got close to Arthur Calwell, and there were times, perhaps with Calwell’s knowledge and acquiesce, that Leo broke the strict quotas on Jewish refugees and managed to issue exit visas to many more Jews than would have been acceptable under the quota system. The fact is that Leo and his fellow leaders succeeded to such an extent that Australia became home to the largest number per capita of Holocaust survivors after Israel in the world.

Their work and their lives changed over the decades. They became wealthier. They became major philanthropists. They went to live in Israel in the 1960s because Leo had the idea of setting up a textile factory in Ashdod. The factory was built and it thrived, employing, in the end, more than a hundred people.

They continued to work and help run Jewish Welfare and in the mid-1960s, Mina became involved with the Australian Council of Jewish Women, and she eventually became a senior vice-president of the International Council of Jewish Women.

After Leo’s death, Mina never remarried. In the 1980s she became involved in making the dream of a Holocaust Centre in Melbourne a reality and the main hall of the Holocaust Centre, when it opened in 1984, was named after her husband.

In conclusion, let me just say something about Margaret Taft and her body of work. I wrote the forward to the book she wrote with Andrew Markus, Second Chance: The Making of Yiddish Melbourne. It is a terrific and important book, especially for the Melbourne Jewish community.

Now comes this book, which is essentially set in Melbourne, and which is about the lives of two quintessentially Melbourne Jews. Margaret is surely now one of the leading chroniclers of the Melbourne Jewish community. In this book Margaret Taft is telling the story of our Jewish lives. It gives me great pleasure to launch her book, Leo and Mina Fink, For the Greater Good.

This is an edited version of the speech Michael Gawenda gave in Melbourne on March 21 to launch Leo and Mina Fink, For the Greater Good, by Margaret Taft, published by Monash University Publishing.

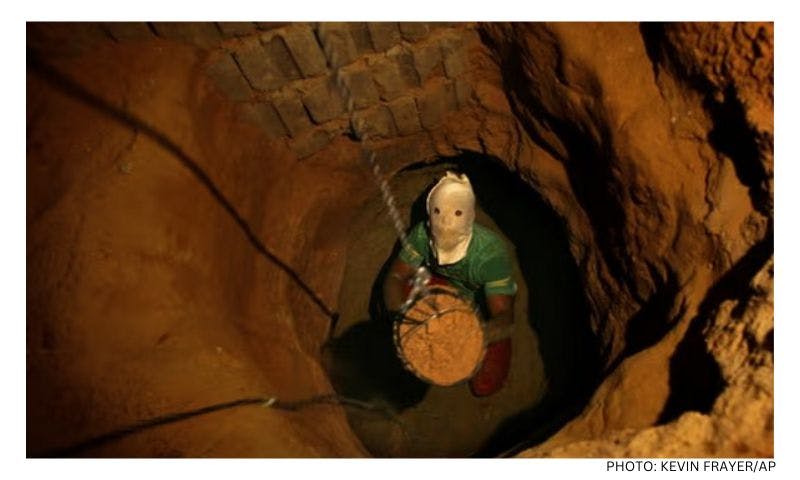

Photo: Leo and Mina Fink in Bialystock,1932

All images courtesy of the Fink family