Published: 16 July 2021

Last updated: 4 March 2024

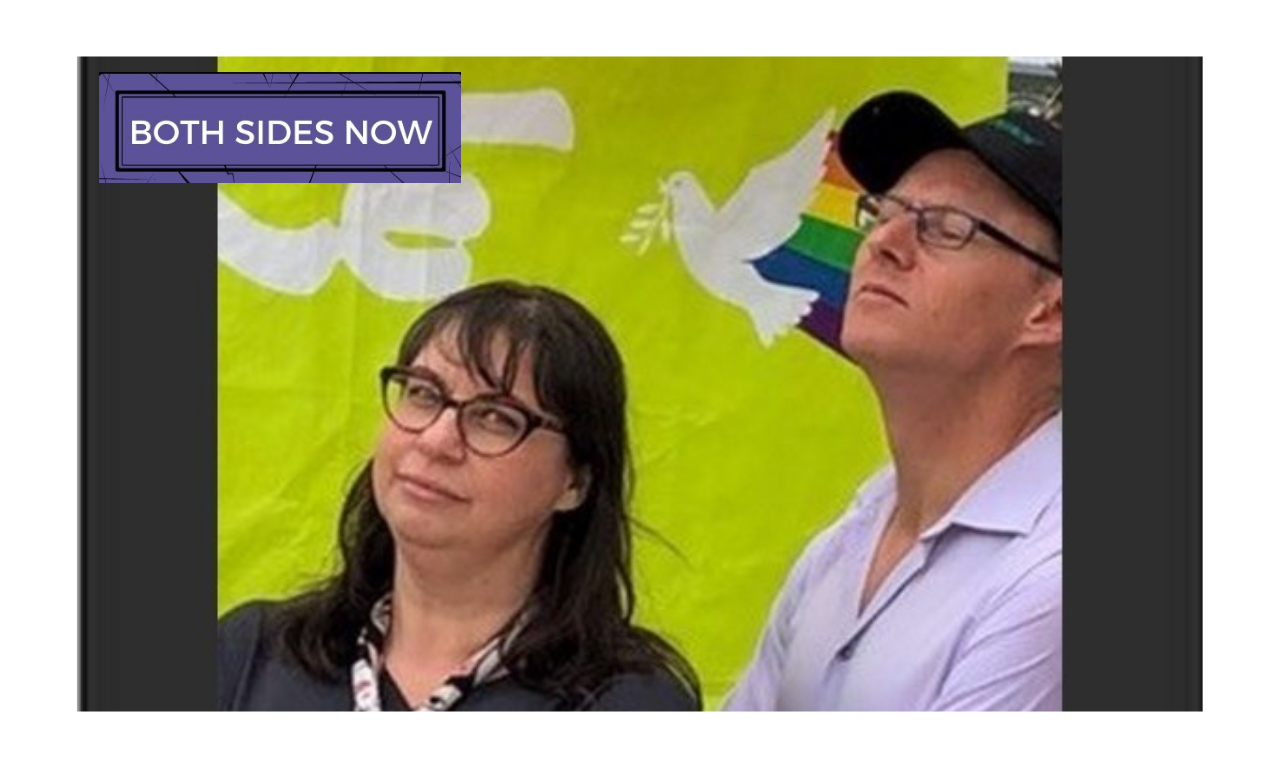

Greenpeace Australia chief David Ritter and human rights academic Melissa Castan have 'an affinity': they can stop a conversation and two weeks later take up where they left off

David Ritter, 50, is the CEO of Greenpeace Australia Pacific. Melissa Castan, 55, is an Associate Professor of Law and a Deputy Director of the Castan Centre for Human Rights Law at Monash University.

DAVID

Paradoxically, Judaism exerted a presence and a gravity in my childhood as a consequence of its absence. My father was a Shoah escapee. He got out in 1939 on the last Kindertransport from Prague. His brother, mother and father also got out by various routes but most of the rest of the family stayed behind and were murdered.

Although my father had experienced quite a liberal Jewish upbringing and education, his family were practising Jews. But after the catastrophe of the war, my father’s atheism and ideology of non-conformism meant he no longer had an interest in practicing Judaism. And my mother was not Jewish.

Yet although Dad rejected the religion, things were always ambiguous in that he was loudly proud of his origins as a Jew and as a refugee.

When, in grade two, a teacher in my state primary school asked the

class about our religion, I put up my hand and said, “Well, I’m half Jewish.”

That night, when I reported this event to my parents, it was a bit of a moment in my household because it forced the contradiction that, “no, we’re not Jewish because we don’t observe but yes, we are Jewish because of the background”.

When your legacy is the story of escape from genocide and the refugee experience, that weighs on you and is lopsided if it does not come with the rest of the identity.

The broader question of Judaism came in my twenties when I worked for Marcus Solomon, an orthodox Rabbi and brilliant lawyer who was a partner at the firm where I was articled.

It was Marcus who asked me straight out, “Have you ever been interested in the wider question of what it means to be Jewish?” I think I was ignorantly dismissive because I’d absorbed a whole lot of the reflexive secularism of our times. He planted a seed.

At the same time, I was a native title lawyer, spending lots of time on Country with Indigenous people. I suppose taking instructions from my own clients about their lived experience of culture made me question my own origins and place in the world in multiple ways

The other thing that became significant was the role played by various Jewish people in relation to the Indigenous struggle for land rights in Australia. Bryan Keon-Cohen and Ron Castan were two of the three barristers in the final Mabo case. Arnold Bloch Leibler played a major role in some native title litigation. Garth Nettheim was one of the leading thinkers in the area.

Through the force of their example, advocates of this kind hinted at Judaism implying a set of commitments to human flourishing.

It was in my role as the principal legal officer at the Yamatji Marlpa Land Council where I bowled up to Melissa Castan at a conference commemorating the 10-year anniversary of Mabo and asked her if she would sign my commemorative poster. Her father, Ron, had tragically passed away, but Melissa worked on the case as a student.

Melissa, very embarrassed, said something like, “what’s all this about?” I adored her on the spot, because she is such an extraordinarily warm person.

Melissa is wonderful to talk with about ideas, current events, strategy, what motivates a person, but all of that is quite cerebral. Our friendship is anchored in her generosity and willingness to give advice, draw on her experience and talk about the things that really matter: how you bring up children, choose your school, think about being a parent in the world, and allocate your time.

It’s the great gift of a multifaceted friendship with Melissa and her husband Rob Lehrer, whom I also regard as a dear friend.

Melissa is an extraordinarily humble person; she’s kind and wise, and Judaism is part of the ambience of our friendship. A little through Marcus and a lot through Melissa and others, I feel part of a wider fabric of belonging and in some strange way at home, and that feels incredibly precious.

MELISSA

My relationship with David is one of those relationships that can continue on an asynchronous level so you can stop the conversation and two weeks later you just take up where you left off. It doesn’t really matter what’s happened in the meantime.

At our essence, There’s an affinity between us. It’s where you find likeminded people who understand you and you understand them. Each time you see them you reconnect, and you don’t have to re-establish ground rules each time. You just keep rolling forward.

We basically talk at each other at a very high pace and part of it seems to involve me telling him what to do and him following what I’ve advised him to do and then him telling me a year later that he took my advice, to which I’m generally horrified that anyone would actually find my advice useful.

Advice goes from the trivial to the serious. Should he get a cat or a dog? This year near Passover, we gave him two different versions for the Haggadah and told him, “This one’s good for the kids and this one’s good for you. It doesn’t matter what you do, just do something with it.”

He got back to us a month later and said, “We had Seder for the first time in the Ritter family for maybe 50 years!” And I said, “Fantastic, what did you do?’ and he said,” I don’t know but we did it.”

My childhood was very clearly a culturally Jewish childhood but we didn’t go to a Jewish day school. Our family was very alive to our Jewish history and our grandparents’ stories and we practiced Jewish traditions but in a fairly modern and cultural practice rather than any form of religious orthodoxy or traditional practice.

In my teenage years I was a member of Hashomer Hatzair, which was left wing and explicitly directed to social justice and social change. My expression of my Jewish culture and persona was through that youth movement community. My parents thought that was a constructive way to have engagement in Jewish and Israel issues.

I don’t know whether they agreed with everything Hashi stood for but they thought it was a good way for a wayward teenager to spend their Sunday afternoons.

As an adult, Judaism is important and foundational for me but it’s not something that I have to search out or articulate or manifest, it just is within. Judaism informs my family life and my parenting but again it’s at a very foundational level about the importance of family and of children in the family and of the intergenerational relationships.

I think David has a very deep, serious, vital, intellectual energy and if he shares that with you, that is a very precious thing to be included in, or to be invited into how his mind works. He’s a very sincere person and a very grateful person. But he has a very big mission in his life and the mission is very clearly articulated and very manifest; not many people can express that.

And it’s hard work, because when you have a mission like that, you have to persist at it over time. His mission is a lifelong mission. To have that degree of integrity and purpose is really impressive.

There is a verse from Pirkei Avot that’s very apt to characterise David and his work. Do not be daunted by the enormity of the world’s grief. Do justly now. Love mercy now. Walk humbly now. You are not obligated to complete the work but neither are you free to abandon it.