Published: 5 October 2019

Last updated: 4 March 2024

And who by fire (Leonard Cohen)

And who by fire

who by water,

Who in the sunshine,

who in the nighttime,

Who by high ordeal,

who by common trial,

Who in your merry merry month of May,

Who by very slow decay,

And who shall I say is calling?

Unetanneh Tokef - (writer unknown)

…And the great shofar will be sounded

and a still, thin voice will be heard.

Angels will be frenzied,

a trembling and terror will seize them

and they will say, ‘Behold, it is the Day of Judgment, to muster the heavenly host for judgment’

…who will die after a long life

and who before his time;

Based on earlier Talmudic traditions, the medieval poem vividly illustrates God counting and calculating people’s deeds during the days of repentance between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. God writes the verdicts of all people in his book and determines their fate. On these fateful moments, when the loud sound of the Shofar is heard followed by the sound of sheer silence, even the angels in heaven tremble as the judgment begins.

The divine sentence does not only refer to the question of life or death, but also specifies the way in which death will come. The level of detail in the poem increases the terror tenfold, conjuring up dreadful images in our imagination: who by water, who by fire; by sword or by beast; by famine and thirst; with upheaval or natural plague; by strangling, or by stoning.

The Jewish tradition attributes the Unetanneh Tokef poem to Rabbi Amnon of Magenza in the 11th century. The poem, according to the legend, was inspired by the rabbi’s soon to come martyrdom and his dreadful tortures by the archbishop of Mainz.

But documents found in the Cairo Geniza attest that the poem existed much earlier to the time of the archbishop of Mainz and was already in use before the time of Rabbi Amnon, on whose life no more evidence is found.

Nevertheless, the legend is a valid reflection to the life of Jews in medieval Europe, a life of great uncertainty, when any appearance of stability and prosperity could quickly turn to times of violence and anguish. The poem offers a sense of potency to the community in its uncontrollable existence. It ends with the words – “but repentance, prayer, and charity annul the severe decree”, providing the people something to do in face of the anxiety and the fragility of life.

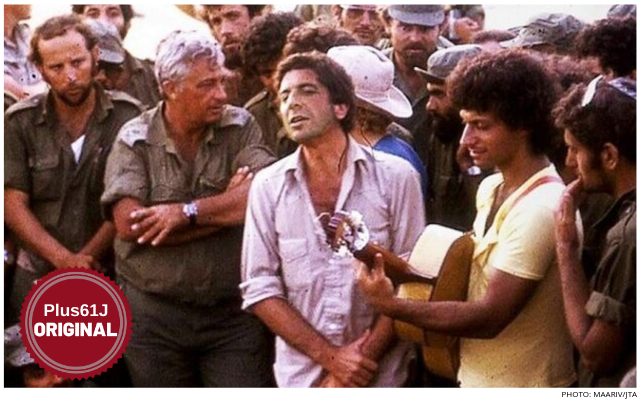

Leonard Cohen wrote Who By Fire in 1974, shortly after his visit to Israel at the break of the Yom Kippur war. But his song does not deal with the instability of the people as a nation. Nor does it deal with retribution or with God’s intervention in people’s fate.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_52Fsr9k3qY[/embed]

He cites the Yom Kippur liturgy and shifts the focus from a theological message to an inquisitive investigation into the mystery of death, almost flirting with the thought of how one may die – by fire, by water, by powder, in the snow or in spring. Instead of the fear to die Cohen practices intimate contemplation with the concept of death.

Various spiritual traditions, amongst which are the Muslim Sufis and the Tibetan Buddhists, see the preparation for death as a first-rate spiritual practice which raises one’s consciousness to higher levels. Cohen explores death on its many forms, perhaps as part of his own personal spiritual journey.

Born in the 1930s, Leonard Cohen grew up in the aftermath of the Holocaust in a religious Jewish family of Eastern European roots. But in the safe and distant Montreal, life was not nearly as risky and uncertain as in the time of his forefathers.

In Who By Fire, death is more a personal and intimate experience. Although well acquainted with the Jewish narrative, as well as with the horrors of the Holocaust and the threats on modern Israel, it was the personal experiences, such as the loss of his father at the age of nine, that seem to have had the greater impact on his life and poetry, reinforcing a sense of the fragility of life.

The modern poem is inspired by the old Unetanneh Tokef in words, style and content. Like many Jewish writers and thinkers before him, Cohen takes old traditions and gives them a different meaning when implanted in his new creation. This new Midrash brings to light the old substance and offers a contrast that enriches the Jewish and popular culture.

In his quest to understand death, there is no answer to “who shall I say is calling?” Polite but alienated, the question keeps hanging in the air, unanswered but ever present. In this new era, and through this new Jewish creation, the questions become more important than the answers.

Photo: Leonard Cohen, centre, performing with Israeli singer Matti Caspi, on guitar, for Ariel Sharon and other Israeli troops in the Sinai in 1973 (Maariv/JTA)