Published: 16 November 2021

Last updated: 4 March 2024

Jaivet Ealom tells Anne Susskind about his harrowing escape from Manus, the book that saved him, Scomo's false piety and the community sponsorship that offers a way out of detention

IN HIS THIRD YEAR away from the horrors of being a refugee, Jaivet Ealom seems happy. Well, as happy as you can be when you have on your mind the fate of about 200 other refugees still trapped in the machinations of Australia’s “Pacific solution”.

Some are in their ninth year in limbo, Ealom says, with no end date in sight, having been transferred from the notorious Manus Island detention centre but still in offshore processing in Nauru and PNG. He calls them “poor souls who have not committed any crime,” and among them are friends he speaks to whenever possible.

This Sunday, Ealom will join a Zoom meeting from Canada, where he is now resettled, in the launch of a campaign to raise awareness of the plight of refugees. Hosted by Melbourne writer Arnold Zable and Professor of Law Kim Rubenstein, the campaign has been organised by Plus 61J Media, Bnei Brith, Stand Up and the Refugee Council of Australia.

Ealom, 28 years old, is the only prisoner known to have escaped Manus and is the author of Escape from Manus, a harrowing book about his experiences, telling the world what successive Australian governments made detainees endure.

Gary Samowitz, a consultant to Plus 61J for the project, says: “Refugees should be welcomed to Australia; we know what it’s like to be in their shoes, we are primarily a community built by survivors and their descendants, and if we can help those who are seeking a safe refuge today… then we must do so.

“Our Jewish heritage and values implore us to act in an ethical and moral way. Supporting and empowering refugees is not just a nice-to-have, rather it is the essence of tzedek (pursuing justice) and tikkun olam (fixing the world).”

Of his new life in Canada, which accepted him with open arms after Australia had put him through the ringer, Ealom said on the phone from Toronto: “It’s actually better than what I’d hoped for.” This is much to my relief, having just finished reading what he’d been through to get there.

A Rohingya person fleeing a genocide in Burma, he’d left home with braces still on his teeth, climbed on a boat unable to swim, the journey paid for by money scraped together by a loving family. He arrived on Christmas Island in 2013, excited and anticipating a helping hand, only to find the law had changed five days earlier so that boat arrivals would “never set foot in Australia”.

After five months, he was transferred to the infamous Manus Island Regional Processing Centre, a “fenced-in dumping ground, a chaotic human zoo.”

Ealom was there when four detainees sewed their lips together as part of a hunger strike (which he joined for a few days himself), and when locals (who had been told the detainees were hardened criminals) attacked the prison.

He was badly injured; fellow detainee Reza Barati had his head crushed by a rock and died; two others lost an eye, and people were hacked with machetes and beaten with clubs. Then came the hair-raising journey to get to Canada, making his way through seven countries without even a valid travel document.

Now he has a meaningful job for an organisation called Needslist, designing software solutions for communities displaced through climate, conflict or poverty, and is doing a political economy degree at the University of Toronto.

His book, published here in June and to be released in Canada next year, is a huge accomplishment, detailing in plain and succinct prose the facts of his life in Burma and then as a detainee (he kept a prison diary, which was useful), as well as the escape.

It is, he says, a “pretty raw” first person perspective, reflecting his disbelief at “how a civilised group of people can do this type of thing to human beings”, at a cost of many billions of dollars to Australian taxpayers, $73,400 alone per night for the ship moored next to the detention centre to house the guards.

Ealom attributes his survival in detention to Victor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning, the 1946 book chronicling the Holocaust survivor’s experience.

Ealom attributes his survival in detention to Austrian psychiatrist Victor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning, the 1946 book chronicling the Holocaust survivor’s experience, recommended to him by a social worker.

One of the psychological deprivations of Manus was that prisoners were allowed to print only five pages fortnightly, so it took him about five months to assemble the book in entirety, with the help of friends’ allowances. In an immense act of self-discipline, he waited until he had accumulated all the pages, then sewed it together before reading.

“Getting to know Frankl inside detention, when there was very little to look up to was eye-opening - the idea of inner control, that through everything, you still have some control of your innermost part, your mind. At that time, I didn’t have any control of my life at all, how I slept, when I sleep, what my days were going to be. Partly because I had no other choice, it was the only choice.

“Humans are probably extremely resilient – we don’t have any set limit, and you don’t know, until pushed, how much further you can go. It’s something like push and stretch.”

Ealom would be lying, he says, if he claimed there were not countless days when he wanted to give up. “But quite a few times, the biggest breakthrough came at the very end, thinking that if I can hold up just a little longer, (until) the breakthrough zone, one minute or one hour after the period when everyone gives up.”

He terminated his hunger strike - “the saddest form of protest, in which you sacrifice your own flesh, blood and bones” - when he recalled Frankl’s time as a “living skeleton” in Auschwitz and decided to eat an apple.

“Something I learnt across this whole journey is that I don’t think humans are terrible as individuals, but (they can be) when they become a group, a collective organised political party, or can say they are just doing a job, where individual responsibility is removed and attributed to something bigger.”

After the 2014 attack, however, he felt a particular individual deserved “a unique portion” of blame – and points the finger at the then Minister for Immigration and Border Protection, Scott Morrison, a “faux-pious” man whose desk sported a “little fishing boat trophy”, the ultimate indicator that “this is a man proud of his cruelty, not even hedging it, displaying it in public.

Scott Morrison's desk sported a 'little fishing boat trophy', indicating that 'this is a man proud of his cruelty, not even hedging it, displaying it in public'.

“He appeared to relish the task of delivering his harsh and punishing policies,” reversing the flow of blame with words such as riot, illegal and escape.

The attack had come from outside the fence, and the diabolical spin about rampaging prisoners was galling, along with the hypocrisy of Morrison and the government’s rhetoric about saving lives at sea, when really, Ealom says, the government was torturing survivors, and the detainee suicide rate in Indonesia (which Australia used as a holding pen) was so high.

In the future, he says, he imagines a time when Australians will look back to Manus’s “dark history” and there will be an apology to the refugees. Although there were some good Australians who helped him (“strangers to me and they took a chance on another stranger”) and he reserves much of his acrimony for the government, he believes that “in the bigger scheme of things, that’s how the world will come to know the Australian general public. It’s being done under your name.”

But more crucial than a future apology is assisting the 200 or so still trapped in the system right now, mostly young men when detained in their formative years. They are the “best of the best”, smart, talented resourceful people, those with the drive and courage it took to get out in the first place.

A close friend, Ealom said, had come out under the Private Sponsorship of Refugees program, a Canadian initiative which allows private people or groups to resettle individuals or families who qualify as refugees.

In the absence of a systemic solution, it seems to be the only option open to individuals at a community level. In the big picture, his solution would be more direct: “Many of them have family in Australia. Rather than sending them half-way across the world, why not just fix up what has been messed up in the first place? That would be my message,” Ealom says.

And, if there is anything else he would like to see, it is that Australians could not at a future time say they did not know what happened.

The Australian Jewish community is reaching across the seas to work with its Canadian counterpart to break the logjam for refugees who have nowhere to go.

“I want to put it out there in first person perspective, with all the nitty-gritty details.” When Ealom arrived in Canada, with just a piece of paper asking for refugee status, the immigration official and the judge he dealt with were astonished by what he’d endured.

In Canada, he says, the Jewish community is very supportive of refugees, and aware and informed about “dark history and cruelty”.

The Australian Jewish community is reaching across the seas to work with its Canadian counterpart to break the logjam for refugees who have nowhere to go and are faced with spending the rest of their lives in limbo.

Ealom has avoided this fate. But has he recovered? “I’m not sure that recovered is the proper word. I‘ve learnt how to accept it as something terrible that happened to me, rather than treat it as something I could recover from.”

ESCAPE FROM MANUS ISLAND: Jaivet Ealom in conversation with Arnold Zable, hosted by Professor Kim Rubenstein: 8pm on November 21

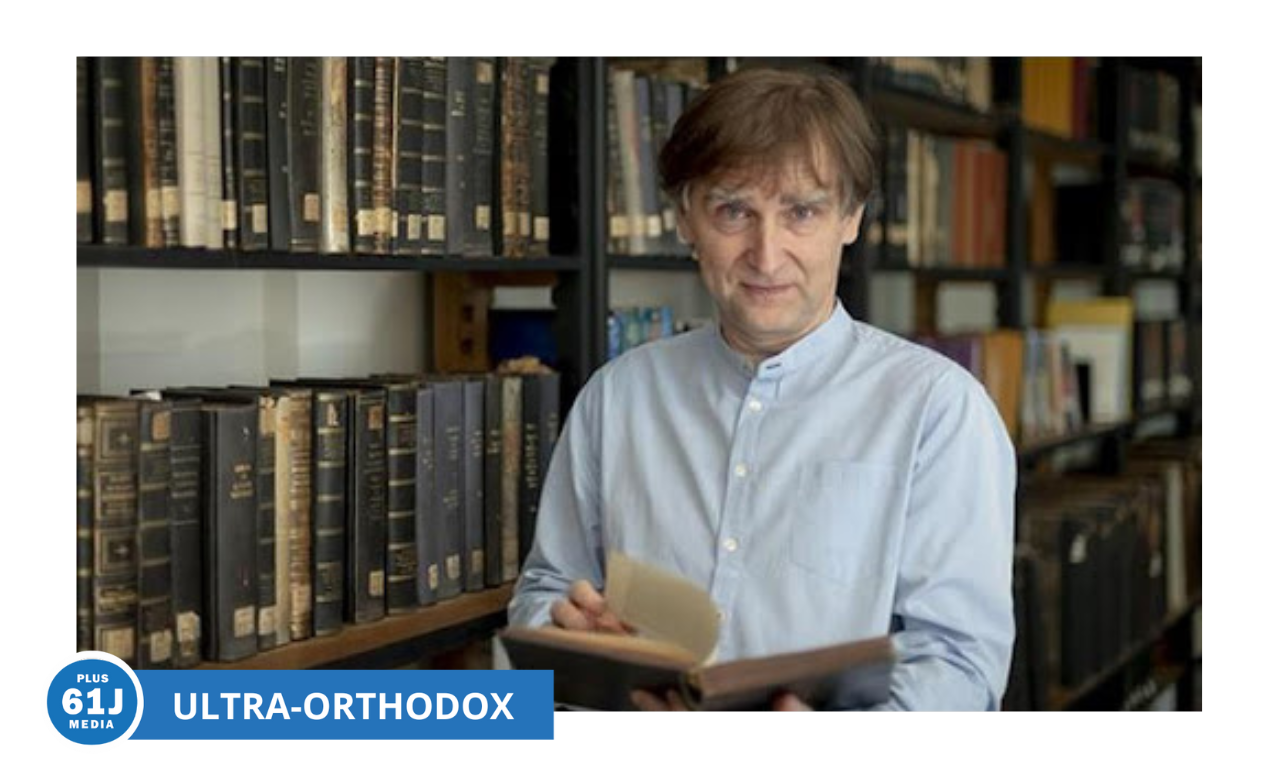

Photo: Jaivet Ealom