Published: 15 March 2022

Last updated: 4 March 2024

KRISTY CAMPION: While security chiefs focus on foreign interference, the extreme Right flourishes in the background, aided by murky online transnational links

THE EXTREME RIGHT in Australia appears to be slipping down the security agenda, with counterterrorism now coming second to foreign interference.

Even though these are overlapping threats, the risk posed by the extreme Right has not diminished. We should be more alert than ever about the dangers posed to sections of the community who are so frequently the subject of extreme Right violence.

It has been three years since “one of New Zealand’s darkest days”, when an Australian citizen stormed two mosques in the city of Christchurch, shooting 100 worshippers: 51 people died, including children, and another 49 people were injured. The terrorist was motivated by right-wing extremism, with an ideology anchored in white supremacist beliefs.

Before the Christchurch attacks, right-wing extremism was not high on the Australian security agenda, and indeed, interest in the threat it posed was relegated to a select few.

This is despite the fact that right-wing extremism has been surging for years and numerous sections of Australian society had been victims of its violence.

This was most clearly demonstrated with the 2016 arrest and subsequent conviction of Phillip Galea on terrorism act offences. Galea, a white nationalist, had been plotting to kill left-wing political opponents and businesses in Melbourne. Around the same time, Ricky White, a white supremacist and member of the Wotansvolk fraternity (a racialised pagan group) was charged with setting fire to a Pentecostal church in Taree. on the NSW mid-north coast. Galea was jailed for 12 years, and White was convicted and jailed.

The Christchurch attack did not come as a bolt from the blue; it was an escalation in an existing pattern of violent behaviour in the Australian community.

Members of the then-United Patriots Front were bearing arms when they were disrupted by law enforcement who saw the chatter on Facebook that the attendees were “packing” and preparing to attend Reclaim Australia rallies in 2015, while a white supremacist arrested for child pornography offences was found to fantasise about mass homicide and was in the process of building a weapons stockpile in 2017.

Amid this, religious and cultural groups were subject to vicious assaults, and their places of worship attacked.

As I established in my early study, A Lunatic Fringe, the extreme Right has developed an ever expanding target base.

Its original target was Jews, who were blamed for subverting Christianity or for being part of a secret conspiracy for world domination. Over the years, it added Australians of Asian descent, the LGBTQIA+ community and other ethnic minorities.

The chief violent outfit of the late eighties, the Australian Nationalist Movement, continued advancing antisemitism. While most of their attacks focused on Australians of Asian descent, they privately held that the greater and more pervasive threat to their vision of society were Jews.

In the decade before the Christchurch attack, the target list expanded again to include the Muslim community. Much like Jewish Australians, Australian Muslims were not a new feature at the time of their targeting.

A common narrative of the time was that that “political correctness had gone mad” in supporting Middle Eastern immigration.

At the same time, Jews remain common targets of extreme Right rage, as demonstrated by assaults and attempted arsons from 2010-13, which included one case of “Satan” being sprayed on a Synagogue wall, and a group attack which left five people injured. They had been targeted because they were Jewish. In 2018, an individual pleaded not guilty to terrorism act offences by reason of mental impairment, after they encouraged terrorism against Jews.

Concurrently, Australians of Asian descent were also targeted, such as the Crazy White Boys attack on a Vietnamese international student in 2012, and the armed robbery, false imprisonment and rape of Vietnamese women a year later by two offenders. These cases were noted to be racially motivated. There was gang-bashing and robbery of homosexuals in Melbourne in 2013.

Attacks against places of Islamic worship were epitomised by the 2010 shooting at Istanbul’s Suleymaniye mosque by members of Combat 18, arson against the Garden City Mosque in Toowoomba in 2015 and Thornlie Mosque, 15kms south of Perth, in 2016, weapons offences in connection with people seeking to attend anti-Islam rallies, and assaults in the leadup to the 2019 terrorist attack in Christchurch.

So, the Christchurch attack did not come as a bolt from the blue; it was an escalation in an existing pattern of violent behaviour in the Australian community, where individuals and groups committed threatening and coercive acts against Australians who did not conform to their ideals.

This demonstrates two important points: first, that there were - and are - individuals and groups in the Australian community who harbour the desire to threaten, harm or kill those who do not conform to their exclusionary ideals. Second, they were - and still are - capable of doing so.

In the three years since Christchurch, the threat has not diminished – but has instead endured.

If we turn to some of the more significant events since that time, we see the continuation of white supremacist ideologies to justify the continued targeting of ethnic, religious, political, and sexual communities.

The extreme Right endures in Australia, in new outfits, new groups, new movements, and with new networks. But their targets remain the same.

In 2019, an individual in Adelaide, bearing a copy of the Christchurch manifesto and obsessed with “patriotic-style” ideologies, was found to be developing improvised explosives. In 2020, two brothers were arrested and charged with terrorism act offences on the south coast of New South Wales. A teenager was arrested after his online activity indicated he was sharing bombing instructions and encouraging others to enact violence against Jews, Muslims, and anyone not of European descent.

A man in Western Australia, wearing a swastika, attacked an Aboriginal woman with a makeshift flamethrower. Members of the Nationalist Socialist Network in Adelaide were found in possession of an explosive device and extremist material, while a man in Orange who owned a neo-Nazi flag was interrupted while attempting to manufacture a 3D firearm.

These significant incidents tell us that the desire and capability to enact significant political violence remains an ever-present threat. But it does not tell the entire story.

Beneath these acts of severe and symbolic violence lie more frequent outbursts of extreme Right rage, which manifests typically as assault and other forms of street violence; graffiti and other forms of property damage; arson, and so on.

This lower level, persistent violence enables right-wing extremists to create an atmosphere of enduring threat against their targets.

The point of this coercion is to force fellow citizens to leave. The extremists do not recognise their targets’ right to live in our country, and they craft narratives which especially cast religious and ethnic communities as being foreign entities which divide and decay current society.

There is a clear need for a national database that captures the array of hate crime, politically motivated violence and terrorism.

Three years after the darkest of days, the extreme Right endures in Australia, in new outfits, new groups, new movements, and with new networks. But their targets remain the same. There is no quick fix to such an established threat.

Our commitment to countering the threat must be robust, consistent, and enduring if it is to effectively provide for the safety and security of all Australians.

Without far reaching commitments and funding, with cross-party support beyond the election cycle, the Australian extreme Right will continue to pursue violent agendas against our fellow citizens.

Combatting the extreme Right requires sustained and informed countermeasures. There is a clear need for a transparent national database that captures the diverse array of hate crime, politically motivated violence and terrorism, and other politically motivated incidences associated with the extreme Right.

Through such a database, we could better understand the ongoing development of the threat, its geographic spread, activities, resources, and transnational links.

As I suggest in my new book, Chasing Shadows, the extreme Right has long fostered transnational networks, which could be a contributing factor to its endurance in Australia. As a result, the transnational sharing of information is vital to overcoming this networked threat.

The sharing of the dataset specifically, and knowledge on the extreme Right generally, would allow Australia to continue the collaboration arrangements developed during the “War on Terror”. This would enable relevant authorities to maintain coverage of the transnational networks of the Australian extreme Right, while also benefiting from the knowledge of security partners.

Such a deep-rooted threat cannot be dispelled in a matter of years. It must be matched with ongoing countermeasures, and cross-party support of politicians to keeping their communities, and their citizens, safe.

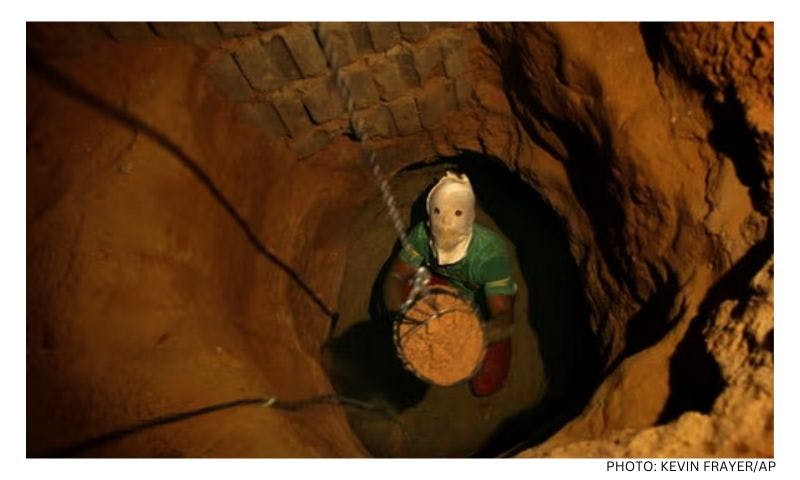

Photo: Police attempt to clear people from outside a mosque in Christchurch, March 15, 2019 (AP/Mark Baker)