Published: 1 November 2021

Last updated: 4 March 2024

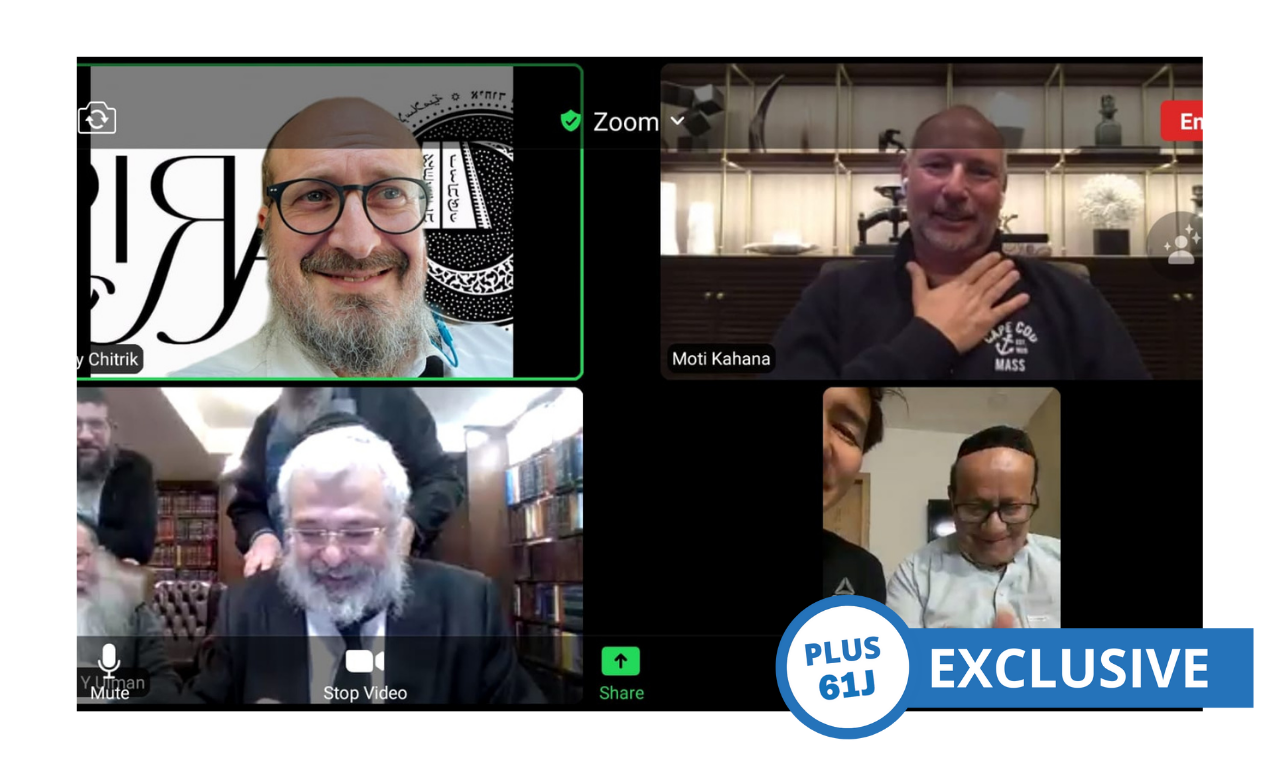

NOMI KALTMANN reveals the key role played by the Sydney rabbinical court and how a Zoom hook-up across four countries granted Zevulun Simantov the divorce that led to his rescue

ZEVULUN SIMANTOV, THE LAST remaining Jew living in Afghanistan, has been the subject of hundreds of articles in the global media since the Taliban took control in September.

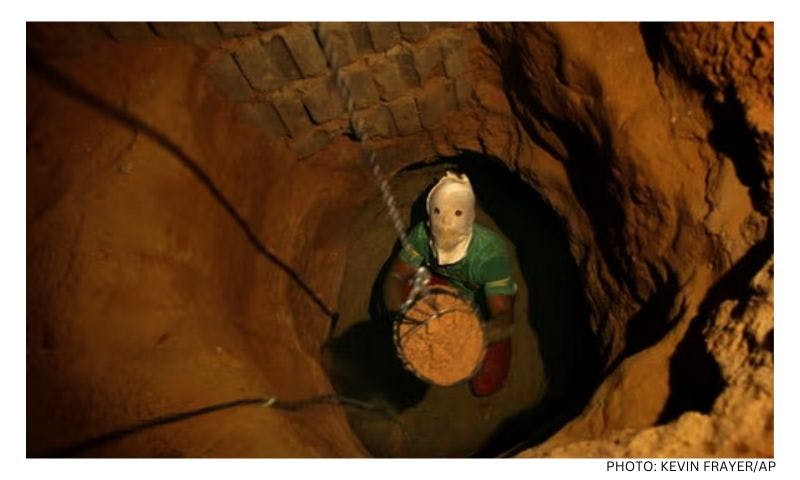

Having moved to Kabul several decades ago, he stayed in the city during the previous Taliban takeover, despite being briefly jailed at one point, and refused all offers to leave the country. Even though his family members had long left the country, and the other remaining Jew died in 2005, Simantov had been happy living among his Afghan neighbours and friends.

So his high-profile departure from Kabul, where he had long been a magnet for tourists and journalists, captured the international spotlight.

Now The Jewish Independent can reveal the central role played by senior members of the Sydney Beth Din and the dramatic chain of events, involving rabbis and rescuers spread across the globe, that led to his journey to safety.

Rabbi Mendy Chitrik, the Chairman of the Alliance of Rabbis in Islamic States, lives in Istanbul, Turkey. He has known Simantov for many years and over the past decade provided him with Matzah and other Jewish supplies.

“[Our Alliance] are in touch with Jews around the world living in Muslim countries and we provide them with any assistance that they may need,” Chitrik told The Jewish Independent.

“Originally, Zevulun had no intention of leaving Afghanistan,” says Chitrik. “However, as the situation deteriorated, he understood that he may be kidnapped, or held for a ransom, and it could become very difficult to release him.”

However, Chitrik says he made it clear to Simantov that the pre-condition for organising his rescue was that he must grant a gett [Jewish divorce] to his ex-wife who was living in Israel. At the time, she had been waiting for more than 20 years and the rescue mission provided an opportunity to resolve this longstanding issue.

Rabbi Ulman is very innovative, and is held in high regard in all rabbinical courts around the world.

Together with Moti Kahana, an Israeli-American businessman who operates a security company that specialises in rescuing people from high-risk countries, a team was assembled to organise Simantov’s evacuation.

Kahana’s organisation called “GDC Inc” was founded in 2011 and has taken an active role in conducting humanitarian rescues from Syria and other complicated areas in the Middle East.

“Getting Zevulun out was difficult: he started negotiating with us when we came to rescue him,” Kahana told The Jewish Independent.

“In the end, I told him the story of Steven Sotloff [the Jewish American journalist kidnapped and publicly beheaded by ISIS] in 2014 and said [ISIS] will kidnap you and sell you to the Jewish people. Or if that doesn’t work, they will chop your head off because they are fighting for power and they will negotiate with us for your body,” says Kahana.

Despite all the warnings, Simantov was not yet compelled to leave Afghanistan.

Simantov turned down the first rescue effort organised by Kahana, which ended up saving the Afghan women’s soccer team instead.

Kahana notes, “In the end, Zevulun’s neighbours convinced him to leave. They were stressed when they heard gunfire close by [to where they were living], so he finally agreed to evacuate. We ended up rescuing him and 30 of his neighbours in a mini-bus.”

After crossing into Pakistan, Simantov knew that it was time to give his wife the long awaited gett.

“Zevulun said that he hadn’t given the gett for over 20 years because he was in Afghanistan and he didn’t have access to any rabbis or a Beth Din [rabbinical court],” says Kahana. “But he was happy to do it, if it could be organised.”

The job of organising this complicated proceeding fell to the Sydney Beth Din, under the rabbinic supervision of Senior Dayan [senior rabbinic judge] Rabbi Yehoram Ulman. Over the years, the court has developed a specialty in dealing with very rare situations which have nuanced Jewish law complications.

How did an Australian rabbinic court, on the other side of the world end up facilitating the gett proceedings for Zevulun Simantov?

“Rabbi Ulman is the teacher of my Dayanut program [rabbinic judges training program], which has students from across the globe, including me, and I hold him in very high regard,” says Chitrik. “He is very innovative, and I know that he is held in high regard in all Batei Din [rabbinical courts] around the world.”

While Rabbi Ulman told The Jewish Independent he would not comment on cases that come before him at the rabbinic courts, the Sydney Beth Din is known around the world for dealing with many situations where there is no local Beth Din, or in cases where a husband cannot travel to a place where there is a functioning Beth Din.

In addition to dealing with cases from Australia and New Zealand, the Sydney Beth Din also has jurisdiction over many Asian countries and has developed a reputation for its expertise in resolving complicated areas of Jewish law relating to family matters.

According to Chitrik, an international video call took place over Zoom with Chitrik in Istanbul, a panel of rabbinic judges in Sydney, Simantov and his Dari translator in Pakistan and businessman Motti Kahana in New York City. It was on this Zoom call that the scribe, witnesses and shaliach [emissary] necessary to complete the gett were all appointed.

As there was no clear timeline when Zevulun could come before a Beth Din in person, the gett authorisation had to be done on Zoom.

“Zevulun gave permission on Zoom [in front of all the parties] which authorised Rabbi Ulman to become his shaliach [emissary] to execute the gett,” says Chitrik.

“Zevulun also provided a signed hardcopy document allowing Rabbi Ulman [and the Sydney Beth Din] to execute the gett, which was FedExed from Pakistan to Sydney two days later,” says Chitrik. “This allows Rabbi Ulman to complete the gett process.”

According to Chitrik, this case is one of the first times authorisations for a shaliach to complete a gett has been provided over Zoom.

“Rabbi Ulman researched [the Jewish law nuances and requirements] extensively because of the unconventional circumstances,” says Chitrik.

“As there was no clear timeline when Zevulun could be before an [in person] Beth Din, the gett authorisation had to be done on Zoom,” says Chitrik.

Now that the gett has been finalised, Simantov has since travelled to Turkey where he is awaiting his visa to visit his siblings and children who live in Israel.

“I think this story is an amazing example of what we can achieve when humanity comes together,” says Kahana. “It shows that we can really get things to actually work.”

Main Photo: Clockwise from top left: Rabbi Mendy Chitrik, in Turkey, Moti Kahana, in New York City, Simantov and his translator in Pakistan, appoint the Sydney Beth Din, via Zoom, to deliver Simantov's gett to his ex-wife (screen capture)