Published: 17 February 2023

Last updated: 5 March 2024

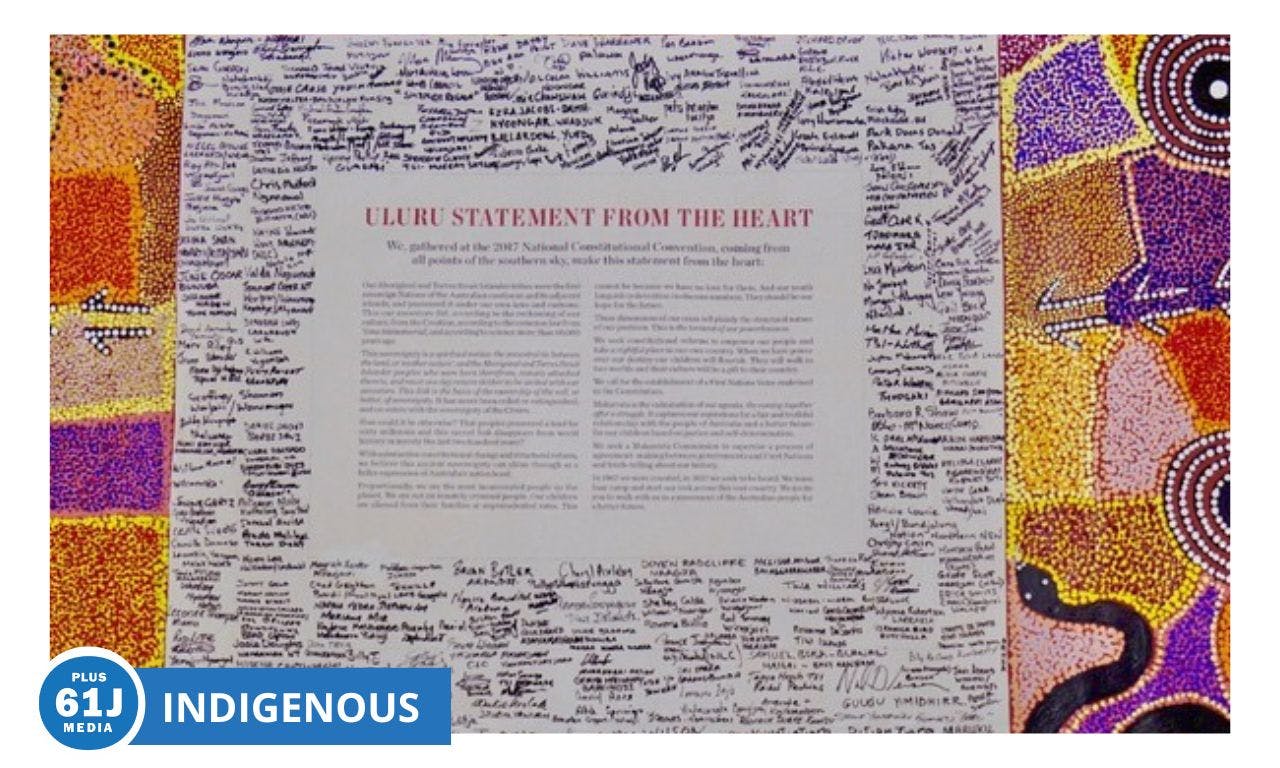

A new book explores faith perspectives on the Uluru Statement from the Heart. RABBI DAVID SAPERSTEIN highlights major Jewish themes.

The Uluru Statement and the proposed referendum on constitutional recognition for Australia’s Indigenous communities are powerful declarations. The referendum will give the Indigenous peoples of Australia a strong voice in the country’s legislative process on issues affecting them.

The religiously insightful and morally powerful essays gathered in Statements from the Soul reflect religion’s ability to transcend political, ideological and cultural differences to forge a moral consensus.

Common themes and values of justice, equity, equality and communal responsibility are expressed in the distinctive texts, language and theologies of the diverse religious and moral approaches presented in these essays.

I see this through a Jewish filter. I found the insights provided by Rabbi Ralph Genende compelling. I was particularly moved by his theme, derived from Jewish thought, that words from the heart speak to the heart – a concept that Archbishop Peter Comensoli, in his essay, attributes to the Catholic theologian John Henry Newman (as it has also been attributed to the 13th-century Muslim writer Rumi).

the plight of the Jewish people over many centuries dreaming for the assertion of our national identity in our historic homeland, should sensitise us to the plight of other such communities.

Allow me to add to Rabbi Genende’s words some additional relevant insights derived from the Jewish tradition and Jewish history, some of which resonate with points made from other faith traditions; some are distinctive to Judaism. First, we Jews are ourselves an indigenous people.

For 3800 years, our destiny has been tied up with the land of Israel. For the past 3200 years, there has been a continuous, unbroken Jewish presence in the land of Israel. Even when we faced ethnic cleansing, when the Babylonians forcibly took the leadership of the Jewish community and their families to Babylonia, and when the Romans forced most Jews into exile from their own land, the attachment remained.

Wherever we lived, Israel and the dream of the return to Israel were fully woven into the culture; the daily and holiday prayers; the rituals, ceremonies and liturgy; and the language of the Jewish people. Indeed, even the terms "Judaism" and "Jew" are derived from the name "Judea" – a major part of historical Israel. Of course, today, we must recognise that the Palestinians and the Bedouin communities in Israel have their own authentic claims as indigenous communities there.

Another insight of Jewish history is that the damage done from oppression and persecution becomes residual trauma and is transmitted down through the generations. A concept we have in many of our religious traditions is represented in the Talmudic phrase that if one destroys even a single life, it is as though one has destroyed the world.

When someone is killed, it means that the entire line of their descendants is also destroyed. This creates a moral responsibility to make restitution in economic, social and educational forms to the victims and descendants of those we killed, enslaved or oppressed. Since the Holocaust, we have seen with sad clarity this insight reaffirmed, recognising the damage that is carried alike by the children and grandchildren of those who perished and those who survived. Such recognition, as well as the plight of the Jewish people over many centuries dreaming for the assertion of our national identity in our historic homeland, should sensitise us to the plight of other such communities within Israel, in Australia and across the globe.

Other Jewish ideas animate this discussion as well: the Jubilee notion of the basic inalienability of the land from its original owners; the special protections in the Bible and post-biblical law regarding the ger, "the stranger" – that is, the non-Jew in the Jewish community; and the Talmudic rule of mipnei darchei shalom, "for the sake of the ways of peace" – the latter two leading to the practice that, where Jews and non-Jews live together, non-Jews should be accorded the social benefits that Jews receive.

These rules recognised that when any group is left behind or is discriminated against or persecuted, there cannot be real peace or stability in a society. Indeed, as it says in Pirkei Avot, an early compilation of moral aphorisms and insights found in the Talmud, "The sword enters into the world because of justice delayed and justice denied." It tells us as well, "The world rests on three things: emet [truth], din [justice or law] and shalom [peace]."

These are the very values implied in the Uluru Statement and called for in so many of these essays: truth-telling about the past, a society based on justice and law, and a commitment to shalom, as the root of the word, sh-l-m, connotes the concept of making whole, healing that which is broken.

Perhaps most on point is the nature of Jewish ideas of repentance, ideas which speak directly to the challenges facing Australia and capture many of the constructive responses that Australia has made.

On Yom Kippur, Jews’ annual day of repentance, the liturgy’s confessional prayer acknowledging our sins is written not in the singular but entirely in the plural ("for the sins which we have committed") – capturing the idea that the revered Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel (the influential 20th-century theologian, social justice champion and Martin Luther King Jr’s closest rabbinic ally) famously framed as, "Some are guilty; all are responsible."

Jewish thought suggests that there are two kinds of sins, each requiring different forms of repentance. Sins against God require sincere regret and a commitment not to repeat the transgression; forgiveness then comes from God. Sins against other human beings, however, require sincere regret, too – but also restitution or reparation to undo the damage done and an apology given directly to the victims, from whom alone forgiveness can come – giving a central role and a voice to the victims in the process of repentance.

Many of these ideas are captured in the Australian Sorry Day practice and in governmental efforts towards Closing the Gap. But ensuring that the voice of the victims is heard is essential, and embodying that commitment in the Constitution adds moral gravitas, political weight and a degree of permanence to such a goal.

This article is an edited extract from Statements from the Soul: The Moral Case for the Uluru Statement from the Heart, edited by Shireen Morris and Damien Freeman, published by La Trobe University Press.

RELATED STORY

Memory, land, justice: Rabbi Ralph Genende on why every Jew should vote for an Indigenous voice (The Jewish Independent)