Published: 25 May 2021

Last updated: 4 March 2024

Eighty years on from 1941, PHILIP MENDES reflects on a massacre that made Iraqi Jews lose faith in their future, prompting a mass migration to Israel. Today only four are left

THE JEWS OF BAGHDAD were subjected to a pogrom during the holiday of Shavuot on June 1-2 in 1941 which arguably resembled the night of the broken glass (or Kristallnacht) in Nazi Germany in November 1938.

The pogrom is known as the Farhud, an Arabised Kurdish word which means “unrestrained massacre, burning, looting and rape by hooligans”, or simply violent dispossession.

About 180 Jews were murdered, nearly two thousand injured, including multiple cases of gang rape, many children orphaned, numerous Jewish properties, businesses and religious institutions damaged and looted, and more than 12,000 people left homeless.

The Farhud was perpetrated by Iraqi soldiers and officers who had returned from an unsuccessful battle with the British army, sections of the police force, and gangs of young people such as members of the paramilitary fascist youth group known as Al-Futuwwa.

This group included women (which was unusual for Arab society) influenced by religious and nationalist fanaticism, and the popular perception of a Jewish alignment with Britain.

These groups rejected the presence of national or religious minorities in the Arab world and regarded the Jews as a fifth column sympathetic to the Western powers.

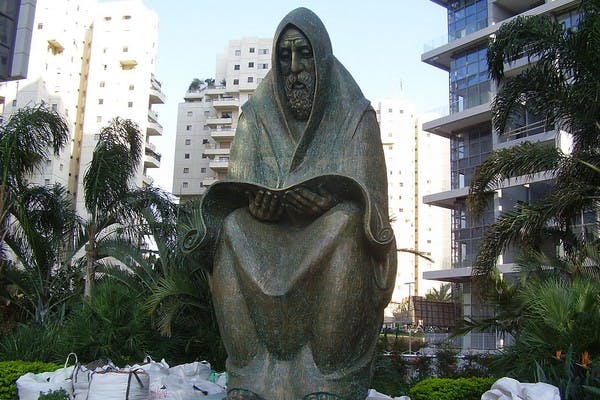

The Farhud caused an enormous shock to the Jews of Iraq, who were one of the oldest communities of the Jewish Diaspora, dating back over 2500 years to the time of the Babylonian exile and the destruction of the first temple in 586 BCE.

They were a relatively prosperous and well-integrated community forming 33 per cent of the population of Baghdad (a total of 80,000 Jews in 1939), which was a higher Jewish proportion than in Warsaw (29 per cent) or New York (27 per cent). The principal city market would shut on the Sabbath.

Jews were particularly prominent in trade, utilising both their knowledge of European languages and contacts with expatriate Iraqi Jews in the countries with which they traded. They also dominated the professions of banking and moneylending, known locally as the Sairafah business. A large proportion of members of the Baghdad Chamber of Commerce were Jewish and Jews played a central role in the entire financial system.

On the other hand, the majority of Jews were poor, and some were destitute. Israeli academic Moshe Gat estimated that 60 per cent of the early 20th century Iraqi Jewish community was poor, and a further 5 per cent were beggars.

Following the establishment of the modern Iraqi state in 1920, Jews contributed prominently to local arts, music and literature. They were represented in the Iraqi parliament, and many Jews held significant positions in the bureaucracy. Sir Sasson Heskel, the country’s first finance minister, from 1921-25, was Jewish.

Jews viewed themselves as Arabs of the Jewish faith, rather than as a separate race or nationality. Only a minority of Jews were sympathetic to Zionism, although more than 5000 Iraqi Jews migrated to Palestine between 1924 and 1944.

Nevertheless, during the 1930s, there was increasing evidence of a decline in Iraqi tolerance for minority groups. The massacre of Christian Assyrians seeking autonomy in August 1933 was widely viewed as an ominous signal.

European anti-Jewish propaganda began to have an impact on Iraq. Anti-Jewish feeling was soon reflected in both official and popular actions. Many Jewish clerks were dismissed from government positions, restrictive quotas were placed on Jewish access to higher education, and Jews were excluded from the army and diplomacy.

Following the 1936 Arab revolt in Palestine, regular public attacks, including bombings, took place against Jews and Jewish institutions such as schools and synagogues. Considerable pressure was placed on Jews to publicly dissociate themselves from Zionist activities.

However, there was no official government policy of discrimination, and the authorities took action to protect Jews against extremist attacks.

The security and confidence of Iraqi Jews was shattered by the pro-German military coup of April 1941, headed by Rashid Ali al-Kaylani, which forced the Hashemite regent to flee the country.

The new regime included some fanatical anti-Semites including the economics minister (and Al-Futuwwa leader) Yunis al-Sabawi, who had assisted with the translation of Mein Kampf into Arabic, and there was a popular stereotyping of Jews as a “fifth column”.

The Farhud was perpetrated by Iraqi soldiers returned from an unsuccessful battle with the British army, sections of the police and gangs of young people.

The coup was quickly defeated and its leaders exiled by a British army occupation, but before losing power their supporters painted the homes of Jews with a red hamsa (palm print) so that they could easily be targeted by the perpetrators of the Farhud.

The anti-Jewish rioters were influenced by a number of factors. One was ongoing incitement by a group of about 400 Palestinian and Syrian émigrés residing in Iraq. The Palestinians were mainly doctors, teachers and politicians who had fled to Iraq after the failed 1936-39 uprising against the British. They were led by the extremist Mufti of Jerusalem, Haj Amin el-Husseini, who would later collaborate with Hitler’s Final Solution.

The Palestinian poet Burhan al-Din al-Abbushi wrote inflammatory verses accusing the Jews of killing and violating Arab women and children in Palestine. These verses were read publicly in mosques and schools, at demonstrations and on the radio, and appear to have provoked much anti-Jewish hatred.

Another factor was the anti-Jewish propaganda distributed in Baghdad by the German Nazi envoy Fritz Grobba, who purchased a Christian Iraqi newspaper which then serialised sections of Mein Kampf in Arabic.

Also important was the anti-Jewish campaign by local Iraqi nationalists, including leading officials in the ministry of education, and the anti-Jewish speeches by local clerics at specific mosques in Baghdad on the day of the Farhud.

The British made the cynical political decision to delay the timing of its intervention to restore order lest it be labelled as a friend of the Jews. British soldiers occupied the suburbs of Baghdad on May 29 but waited until the afternoon of June 2 to re-enter the city.

It appears the British later acted with similar malevolence in failing to act to prevent anti-Jewish riots in Libya in November 1945 and Aden in December 1947.

Many Iraqi Jews expressed a terrible sense of betrayal. Some had served as doctors and officers in Rashid Ali’s army during the battles against the British, and Jewish merchants (almost certainly under some pressure) had donated generously to the armed forces. They expected a more positive outcome from their service than this horrific massacre.

The Farhud caused a lasting trauma, and an ongoing fear of recurring pogroms which led many Jews to believe there was no future for them in Iraq.

Many of those killed and injured in the Farhud were attacked by locals they knew. Government hospitals often refused to treat the injured Jews, and some were later told by Jewish nurses that the injured were poisoned by government hospital doctors on the orders of the Dean of the Faculty of Medicine.

Some wounded Jews were transferred to alternative hospitals, populated by mostly Jewish doctors, for their own safety. Others gave jewellery, gold and money to their neighbours in trust, who then refused to return the property.

Yet there were hundreds of Jews who recalled with gratitude the bravery of Muslim neighbours who respected the tradition of Arab hospitality to protect them. Many Muslims living in mixed neighbourhoods provided refuge to dozens of Jews in their homes.

Mordechai Ben-Porat (later a long-standing member of the Israeli Parliament) recalled the wife of his Muslim neighbour, Colonel Taher Mohammed Aref, bravely threatening rioters with a pistol and hand grenade to dissuade them from advancing.

A letter of gratitude was written by the president of the Jewish community of Basrah thanking Shaikh Ahmad Bashasyan – the former lord mayor of Basra – and his family for protecting Jews during the Farhud.

The new Iraqi government took steps to restore law and order. From late 1941, the leaders of the Farhud were jailed or exiled, and some were executed. An official inquiry attributed the Farhud to a number of factors, including German propaganda and the influence of Palestinian and Syrian exiles led by the Mufti of Jerusalem. The Jewish victims were awarded a small amount of financial compensation.

The Jews were shocked by the silence of the Iraqi Arab intelligentsia, many of whom defended the Rashid Ali regime, and condemned the execution of some of its key leaders.

No literary works by Arab writers mentioned the Farhud, though some popular songs were compiled before and during the Farhud expressing hatred for the Jews and celebrating the theft of valuable property from the supposedly wealthy Jewish merchants.

According to Israeli historian Shmuel Moreh, from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the Farhud constituted a “decisive and tragic turning point” for the Jews of Iraq and destroyed what he calls the “Jewish delusion that they could live in Iraq as citizens of equal rights with the Muslims”. He argues that the Farhud convinced most Iraqi Jews that Zionism was the solution.

Similarly, French historian Georges Bensoussan asserts that the Farhud caused a lasting trauma, and an ongoing fear of recurring pogroms which led many Jews to believe there was no future for them in Iraq.

The Farhud convinced many younger Jews to turn to either Communist or Zionist solutions.

The outbreak of the 1948 Israeli-Arab war accentuated the already precarious position of Iraqi Jewry, which was subjected to both official measures of anti-Jewish discrimination that deprived Jews of their civil and economic rights and livelihoods, and populist attacks including of bombings.

In 1950-51, more than 120,000 Jews (95 per cent of the Jewish population) left Iraq for Israel via the airlift known as Operation Ezra and Nehemiah.

They formed a major component of the nearly one million Jews – known as Mizrahim – who left Arab countries in the two decades following the 1948 war. They now constitute the majority of the Jewish population of Israel and often lean towards the hawkish side of the political spectrum.

Today, only four Jews remain in Iraq, a tiny remnant of this formerly large and ancient community.

Main photo: The Farhud, during Shavuot, June 1-2, 1941 (Yad Ben Zvi & Beit Hatfutsot)