Published: 7 December 2021

Last updated: 4 March 2024

MATI SHEMOELOF says one of the aims of his new novel, The Prize, is to expand the boundaries of the Hebrew language beyond Israel’s borders

JERUSALEM’S NOVEMBER SKY turned blue and the temperature dropped. I put on my yellow sweater and caught a taxi from the hotel to the Leo Baeck Institute, where the virtual launch of my novel, The Prize, was about to begin. In Berlin, where I live, it’s been a traditional autumn, with dark skies and endless burning leaves falling from the trees. In Jerusalem, the trees are always green.

There were five speakers at the launch. The two in Germany were ready to begin, a third had just arrived from Berlin and there were two Israeli speakers. Most of them spoke about the history of Germany’s Jews. This mingling of Israeli and German identities resembled the plot of my novel, which focuses on the tension between the Israeli and German societies.

In the novel, the German government announces a new international prize for Hebrew writers, the Berlin Prize for Hebrew Literature, which will revive the Hebrew Literary Centre in the city. Between the two world wars it flourished and there were more Hebrew publishers here than in Palestine.

Chezi, an Israeli-Jewish guy of Iraqi descent who moved to Berlin to be with Helena, his German wife, is the first winner of the award for his book, Staying in Baghdad. His win provokes a political storm in Israel. Coincidentally, on the morning of his win, Helena is booked in for an abortion

At the launch, I looked at my Bagdad-born mother, who came with her husband. She was proud of me. She was one of the main reasons I wanted to write this novel. I wanted to bring something from her character into the plot.

Chezi’s mother, Amira, a traditional Jewish-Iraqi Israeli-mother comes to Berlin to try and save Chezi and Helena’s marriage. Amira’s character is based on my mother.

The Leo Baeck Institute in Jerusalem researches the history of German Jews. It was the first time that I was regarded as a German Jew with words from the German and Israeli scholars.

Suddenly, the fact that the novel was written in Berlin was more interesting than me being an Israeli writer.

I married a woman from East Germany. In the book, Helena is from West Germany. I wanted to write about the meeting point of the elitist West German with the poor Israeli writer. I wanted to catch the zeitgeist, the sign of the time, of the Israeli immigration to Berlin. How we, the immigrants bring new ideas about class and ethnicity into German thought.

At the launch, Dr Yemima Haddad, from the School of Jewish Theology in Berlin, said Chezi was a lower-class guy who wanted to use his literary win as a ticket into the higher German class.

Helena, who was born into a bourgeois family in Stuttgart, betrayed the hopes and aspirations of her parents. She grew up as a talented pianist but did not realise her potential. She abandoned her promising musical career and found herself working for an organisation helping refugees.

Until 2014, the Sapir Prize was open to all Israeli citizens; after that the prize was limited to writers who live in Israel.

Because of Covid restrictions, not many people attended the launch. But hundreds from around the world watched online. Today, there are many Hebrew writers outside of Israel. And they wanted to know more about that new diasporic situation through the literary discussion.

In my book, the prize is open to anyone who writes in Hebrew. In contrast, the Sapir Prize, Israel's most prestigious and lucrative literary award for Hebrew literature, is given only to Israeli citizens who write in Hebrew.

with little noise in the media, the borders of the Hebrew language were reduced to the geographical borders of Israel.

Until 2014, the prize was open to all Israeli citizens, regardless of where they lived. That year, the prize was won by Ruby Namdar, who lives in New York. From the following year, the prize was limited to writers who live in Israel.

Thus, and with little noise in the media, the borders of the Hebrew language were reduced to the geographical borders of Israel. With his book, I wanted to challenge this reversal and open new diasporic horizons and try to imagine what would have happened if the Hebrew literary centre had moved from Israel to another country.

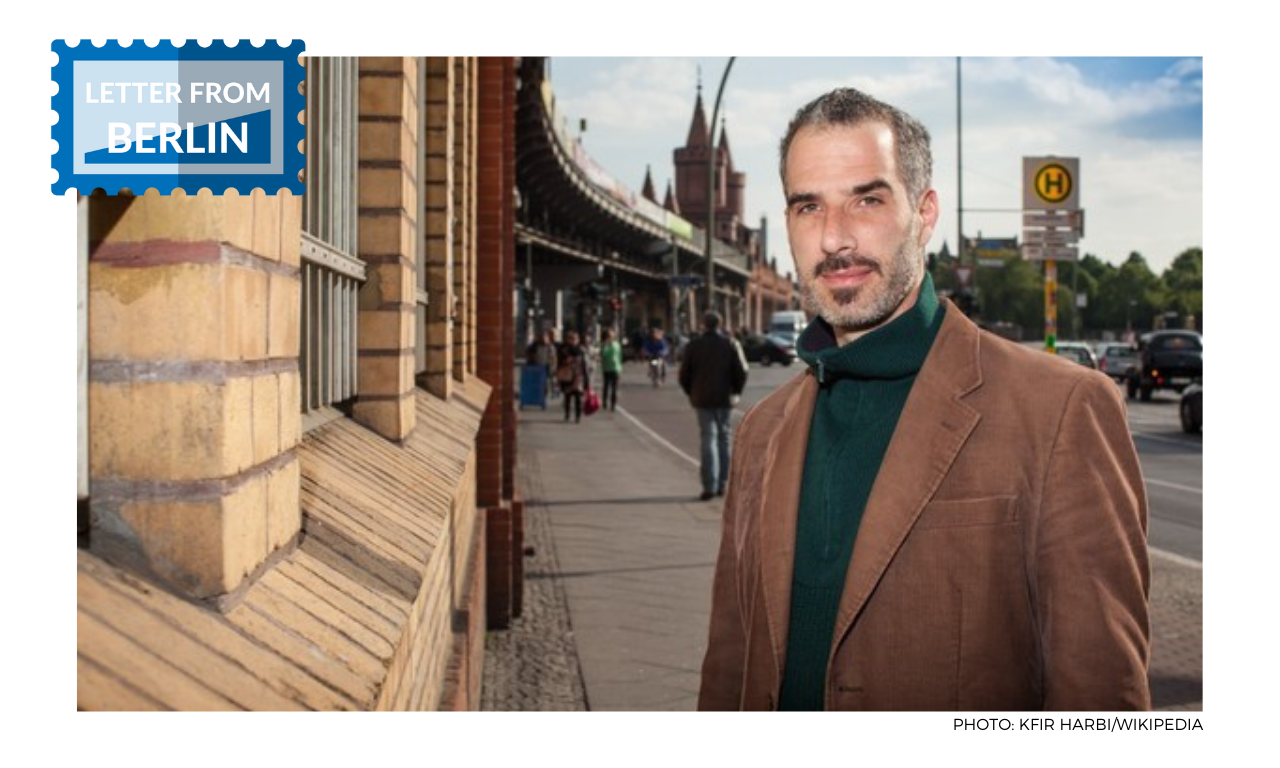

Photo: Mati Shemoelof (Kfir Harbi/Wikipedia)